CORRESPONDANCES

13

forumdoc.bh.2024

28º Festival do Filme Documentário e Etnográfico, Brazil

28º Festival do Filme Documentário e Etnográfico, Brazil

SCREENING OF A FIDAI FILM

November 21st - December 1st 2024

A Palestina e os arquivos que ardem, a text by Carla Italiano e Carol Almeida published in the catalogue of forumdoc.bh.2024.

︎︎︎In Portuguese

︎︎︎In English

︎︎︎In Portuguese

︎︎︎In English

12

Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do cinema, Lisboa

INDIELISBOA: RETROSPECTIVE KAMAL ALJAFARI

May 24th - 31th 2024

Honouring the cinematographic work of Palestinian director Kamal Aljafari

In partnership with Cinemateca Portuguesa, and with the presence of visual artist and filmmaker Kamal Aljafari, we give space to the simple and enormous subversive act of giving visibility to the invisible that is the counter-cinema present in his work. Making present what otherwise seems to be absent from the dominant narrative has always been at the heart of Aljafari’s creation. The author’s work increasingly expands the conceptual and formal delimitations imposed by conventional cinematic grammar and explores a new territory of political cinema that claims a possible “cinematic justice” in the face of reality, which goes far beyond objective historicism, the didactic documentary of social concerns. Subjectivity prevails while the idea of cinema as a tool of colonization and oppression is deconstructed. From a corporeal presence, accompanied by voice-over in The Roof, to hybrid melancholy in what will be his closest work to fiction in Port of Memory, where he has already incorporated, in a dialectical way, excerpts from an American action film with Chuck Norris fighting Palestinian terrorists or the Israeli musical Kazablan. Later, we see him explore poetic and reappropriation potential, diving head first into the most varied archival materials and found footage in the following films, always accompanied by rigorous sound work. A cinematic occupation that functions as an act of resistance.

︎︎︎It’s a Long Way from Amphioxus + An Unusual Summer by Joana Ascensão

︎︎︎Visit Iraq + Port of Memory by Luís Miguel Oliveira

︎︎︎Paradiso, XXXI, 108 + A Fidai Film by Ricardo Vieira Lisboa

︎︎︎UNDR + Recollection by Inês Sapeta Dias

︎︎︎Balconies + The Roof by Antonio Rodrigues

In partnership with Cinemateca Portuguesa, and with the presence of visual artist and filmmaker Kamal Aljafari, we give space to the simple and enormous subversive act of giving visibility to the invisible that is the counter-cinema present in his work. Making present what otherwise seems to be absent from the dominant narrative has always been at the heart of Aljafari’s creation. The author’s work increasingly expands the conceptual and formal delimitations imposed by conventional cinematic grammar and explores a new territory of political cinema that claims a possible “cinematic justice” in the face of reality, which goes far beyond objective historicism, the didactic documentary of social concerns. Subjectivity prevails while the idea of cinema as a tool of colonization and oppression is deconstructed. From a corporeal presence, accompanied by voice-over in The Roof, to hybrid melancholy in what will be his closest work to fiction in Port of Memory, where he has already incorporated, in a dialectical way, excerpts from an American action film with Chuck Norris fighting Palestinian terrorists or the Israeli musical Kazablan. Later, we see him explore poetic and reappropriation potential, diving head first into the most varied archival materials and found footage in the following films, always accompanied by rigorous sound work. A cinematic occupation that functions as an act of resistance.

︎︎︎It’s a Long Way from Amphioxus + An Unusual Summer by Joana Ascensão

︎︎︎Visit Iraq + Port of Memory by Luís Miguel Oliveira

︎︎︎Paradiso, XXXI, 108 + A Fidai Film by Ricardo Vieira Lisboa

︎︎︎UNDR + Recollection by Inês Sapeta Dias

︎︎︎Balconies + The Roof by Antonio Rodrigues

11

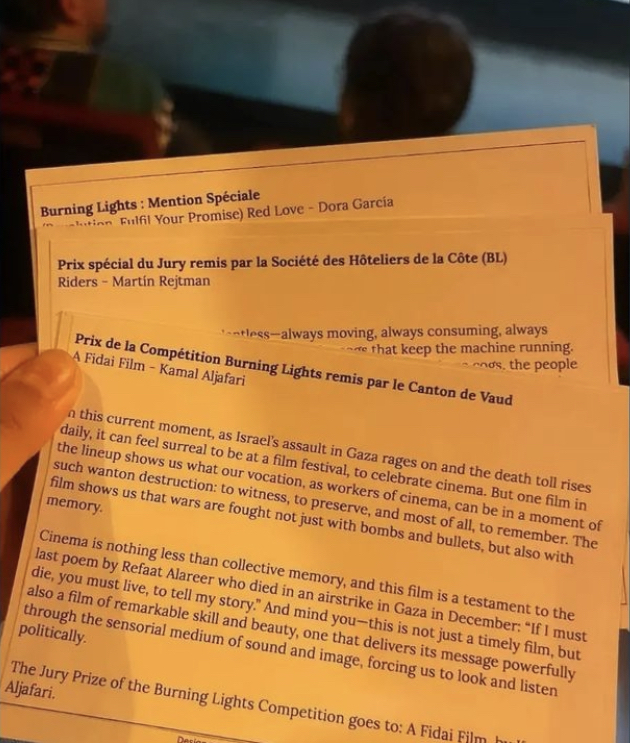

Jury Prize in the Burning Lights Competition

Visions du Réel

Visions du Réel

A FIDAI FILM

April 2024

“In this current moment, as Israel’s assault in Gaza rages on and the death toll rises daily, it can feel surreal to be at a film festival, to celebrate cinema. But one film in the lineup shows us what our vocation, as workers of cinema, can be in a moment of such wanton destruction: to witness, to preserve, and most of all, to remember. The film shows us that wars are fought not just with bombs and bullets, but also with memory.

Cinema is nothing less than collective memory, and this film is a testament to the last poem by Refaat Alareer who died in an airstrike in Gaza in December: “If I must die, you must live, to tell my story.” And mind you—this is not just a timely film, but also a film of remarkable skill and beauty, one that delivers its message powerfully through the sensorial medium of sound and image, forcing us to look and listen politically.

The Jury Prize of the Burning Lights Competition goes to: A Fidai Film, by Kamal Aljafari”.

Jury: Devika Girish, Lyse Nsengiyumva, Eduardo Williams.

︎︎︎A FIDAI FILM — Vision du Réel

Cinema is nothing less than collective memory, and this film is a testament to the last poem by Refaat Alareer who died in an airstrike in Gaza in December: “If I must die, you must live, to tell my story.” And mind you—this is not just a timely film, but also a film of remarkable skill and beauty, one that delivers its message powerfully through the sensorial medium of sound and image, forcing us to look and listen politically.

The Jury Prize of the Burning Lights Competition goes to: A Fidai Film, by Kamal Aljafari”.

Jury: Devika Girish, Lyse Nsengiyumva, Eduardo Williams.

︎︎︎A FIDAI FILM — Vision du Réel

10

Visions du Réel

A FIDAI FILM POSTER

April 15th 2024

Poster designed for Kamal Aljafari in occasion of the world premiere in April 15th for his A Fidai Film at Visions du Réel in Nyon, Switzerland.

︎︎︎A FIDAI FILM — Vision du Réel

︎︎︎A FIDAI FILM — Vision du Réel

09

75 Locarno Film Festival

PARADISO, XXXI, 108, POSTER

July 2022

Poster designed for Kamal Aljafari in occasion of the world premiere in August 9th of his Paradiso, XXXI, 108 at the 75 Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland.

︎︎︎PARADISO, XXXI, 108 – 75 Locarno Film Festival

︎︎︎PARADISO, XXXI, 108 – 75 Locarno Film Festival

08

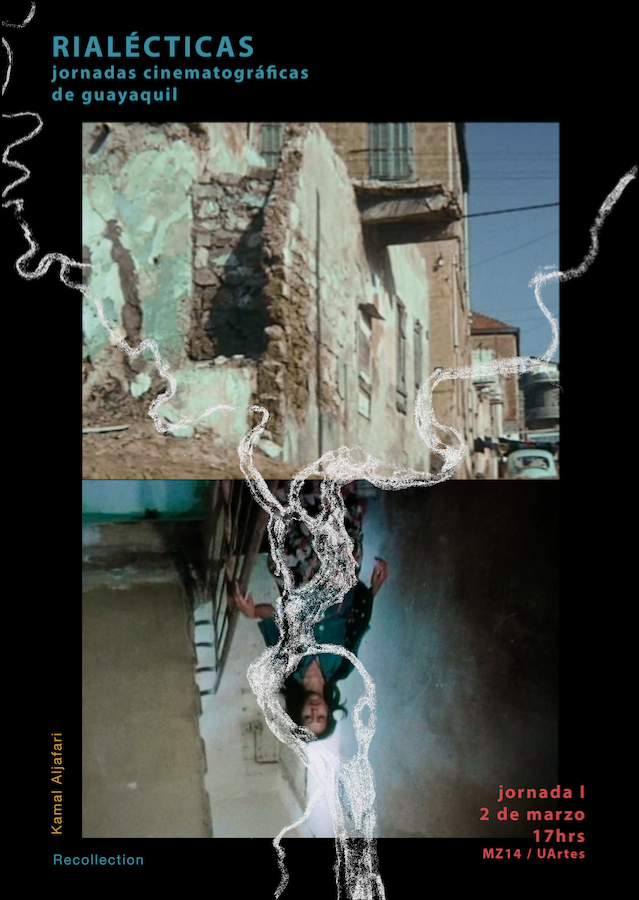

RIALÉCTICAS – jornadas cinematográficas de guayaquil

RECOLLECTION SCREENING POSTER

March 2nd 2022

Poster realized for the occasion of the screening of Recollection in Rialécticas - jornadas cinematográficas de guayaquil.

RIALÉCTICAS es una muestra cinematográfica que a partir de una inquietud geográfica y comprometida con las políticas del habitar, se plantea primordialmente como un diálogo con el territorio que la acoge: la ciudad de Guayaquil. Esta propuesta de programación se llevará a cabo de manera intermitente a lo largo del año.

Abriremos esta muestra con un programa de dos sesiones dedicadas a territorios en ruina, articulados por la emanación de memorias y fantasmas a través de un uso radical del archivo.

Jornada I

Recollection (Kamal Aljafari, Palestina, 70min, 2015)

Él está soñando; y, en su sueño, está filmando. Quien filma está regresando a Jaffa, como podría hacerlo a cualquier lugar catastrofizado.

︎︎︎Recollection screening – RIALÉCTICAS, jornadas cinematográficas de guayaquil

RIALÉCTICAS es una muestra cinematográfica que a partir de una inquietud geográfica y comprometida con las políticas del habitar, se plantea primordialmente como un diálogo con el territorio que la acoge: la ciudad de Guayaquil. Esta propuesta de programación se llevará a cabo de manera intermitente a lo largo del año.

Abriremos esta muestra con un programa de dos sesiones dedicadas a territorios en ruina, articulados por la emanación de memorias y fantasmas a través de un uso radical del archivo.

Jornada I

Recollection (Kamal Aljafari, Palestina, 70min, 2015)

Él está soñando; y, en su sueño, está filmando. Quien filma está regresando a Jaffa, como podría hacerlo a cualquier lugar catastrofizado.

︎︎︎Recollection screening – RIALÉCTICAS, jornadas cinematográficas de guayaquil

07

Letter

ANDRÈ ELIAS MAZAWI

April 15th 2020

Vancouver, BC, Wednesday, April 15, 2020, 7:51PM

& January 28, 2021, 8:45AM

Dear Kamal,& January 28, 2021, 8:45AM

Thank you ever so much for your kindness, generosity and engagement for providing us with the opportunity to watch your yet to be launched film, An Unusual Summer.

“Life must be disrupted in order to be revealed” — announces the film’s text. What starts as an arbitrary set of scenes, shot by a surveillance camera, ends up emerging into a profound tribute to life, time, memory, love, and destitution. Ultimately, An Unusual Summer offers a tribute to the search of meaning to life’s often mundane events, events that we would have otherwise discarded, or deemed meaningless. Small events matter. They contain the emerging meanings of life, their fleeting nature, like a litany of small things that make the big picture clearer, sharper, deeper, and more complex.

Watching An Unusual Summer I found myself wondering what could a surveillance camera reveal. And yet, there’s much more to surveillance than finding offenses and who did what. What emerges are aspects of community life, snippets of memory and fleeting moments of being, each carrying its own histories of time and revelation. The scenes introduce viewers to the vulnerable circularity of life, beyond its presumptions, its claims to power, put simply: in its mundanity. Scenes capture the daily behaviours, the apparently insignificant actions which are catapulted to centre stage in pursuit of a resolution of a hidden actor. In many ways, An Unusual Summer pays tribute to these moments — freezing time in its shadows, and reclaiming stories which would have otherwise dissipated, like steam in the air, leaving very little, if any, signs behind.

As viewers move through the scenes, they familiarize themselves with characters and plots, in which individuals who probably never thought of acting turn into actors despite themselves. Characters who may have been just passing through that segment of space suddenly assume centre stage, a theatrical space of being. In making sense of these sequences, viewers find themselves connecting dots, feeling the suspense, if not the drama, making speculations about what next, who broke that car window. Converging and diverging stories intersect, complement each other. Some stories come into fruition; stories of one line. Others are more complex; others still remain enigmatic, baffling. Not every thing has a purpose. For things to exist, no apparent reason is needed.

I need to think through what I have just experienced by watching An Unusual Summer. Three aspects stand out for me:

First, the fixed camera: it brackets space, time and movement, a feature which is embedded in the functional technicalities of a surveillance camera. A surveillance camera’s relation to space – both in its geographic and temporal manifestations are intriguing. In relation to a given space, within a given time, surveillance cameras offer a total – if not totalizing – view, reminiscent of Bentham’s Panopticon. Yet, it is precisely that feature that turns a banal camera — so frequently used these days — into a powerful tool that reveals more than just surveillance. It allows a zooming in on those fleeting moments where not just stories — but also the individuals who enact them — are revealed in their most intimate and vulnerable aspects of their life and being. Secondly, the processing of the surveillance camera’s footage is intriguing and revealing, both in terms of concept and in terms of techniques used. The “surveillance” footage has been worked out by the filmmaker, transformed. Certain scenes were cut out while others were re-arranged; music and sound over image added; temporalities inverted. Inserted texts infuse into what started as banal scenes the aura of historically situated personal and collective narratives. Emerging into a narrative, the film – as distinct from the “surveillance” footage – is organised around nested stories; stories within stories within stories. Each story reveals a part and contrasts with others until these sequences reach the big stories, the Stories of life, being, love, dispossession, the space’s own transformations, and loss through the story of the fig tree, Kamal’s parents meeting and getting married, childhood memories, refugeedom and dispersion. The result represents simply a tour de force. A final crescendo – similar to Maurice Ravel’s one movement orchestral piece, Boléro (1928) - An Unusual Summer captures through its iterative and accumulating one movement sequences, the big drama that underpins apparently insignificant and plotless acts and scenes, gradually educating our sense perceptions to see and understand life in novel ways.

Thirdly, in as much as the protagonists in the film did not intend to be “actors”, and many may not have been aware of their role as such, the same goes for the filmmaker — Kamal’s late Father, Abedeljalil. At the time of installing and activating the camera he may not have thought about himself as a filmmaker. Nor did he think the footage may one day be useful for any subsequent production, perhaps at most as “evidence” of something. This goes to show that intentionality and filmmaking can be two separate phenomena, situated apart by a time-gap until a third agent intervenes and reframes what appears to be arbitrary footage. It is from within this gap - between the primary intention of Abdeljalil, and his son Kamal’s intentionality - that An Unusual Summer emerges as a vivid testimony to life’s vicissitudes, vulnerabilities, yet also redemptive outlook.

May An Unusual Summer stand as a tribute to the memory of Abdeljalil Aljafari, a time-lapsed collaboration between father and son, and a redemptive one at that.

André Elias Mazawi

06

Film Festival - Video Essay

L’EXTRAIT DE LA SEMAINE N° 19: PORT OF MEMORY (KAMAL ALJAFARI, 2010)

August 17th 2020

L’extrait de la semaine est une série présentée par Zoom Out (zoom-out.ca). Elle invite des amis du cinéma à produire un court texte qui évoque un moment favori de leur histoire personnelle du cinéma.

︎︎︎L’extrait de la semaine, Zoom-Out

TECHINCAL INFO

Texte Nour Ouayda

Montage Olivier Godin

Voix Rose-Maïté Erkoreka

Durée 2’29’’

Licence Creative Commons (CC) BY-NC-ND

Collaborators Nour Ouayda, Olivier Godin

Series: L’extrait de la semaine

Category Audiovisual Essay

Country Lebanon

Language French, Other

Date 2020/8/17

︎︎︎L’extrait de la semaine, Zoom-Out

TECHINCAL INFO

Texte Nour Ouayda

Montage Olivier Godin

Voix Rose-Maïté Erkoreka

Durée 2’29’’

Licence Creative Commons (CC) BY-NC-ND

Collaborators Nour Ouayda, Olivier Godin

Series: L’extrait de la semaine

Category Audiovisual Essay

Country Lebanon

Language French, Other

Date 2020/8/17

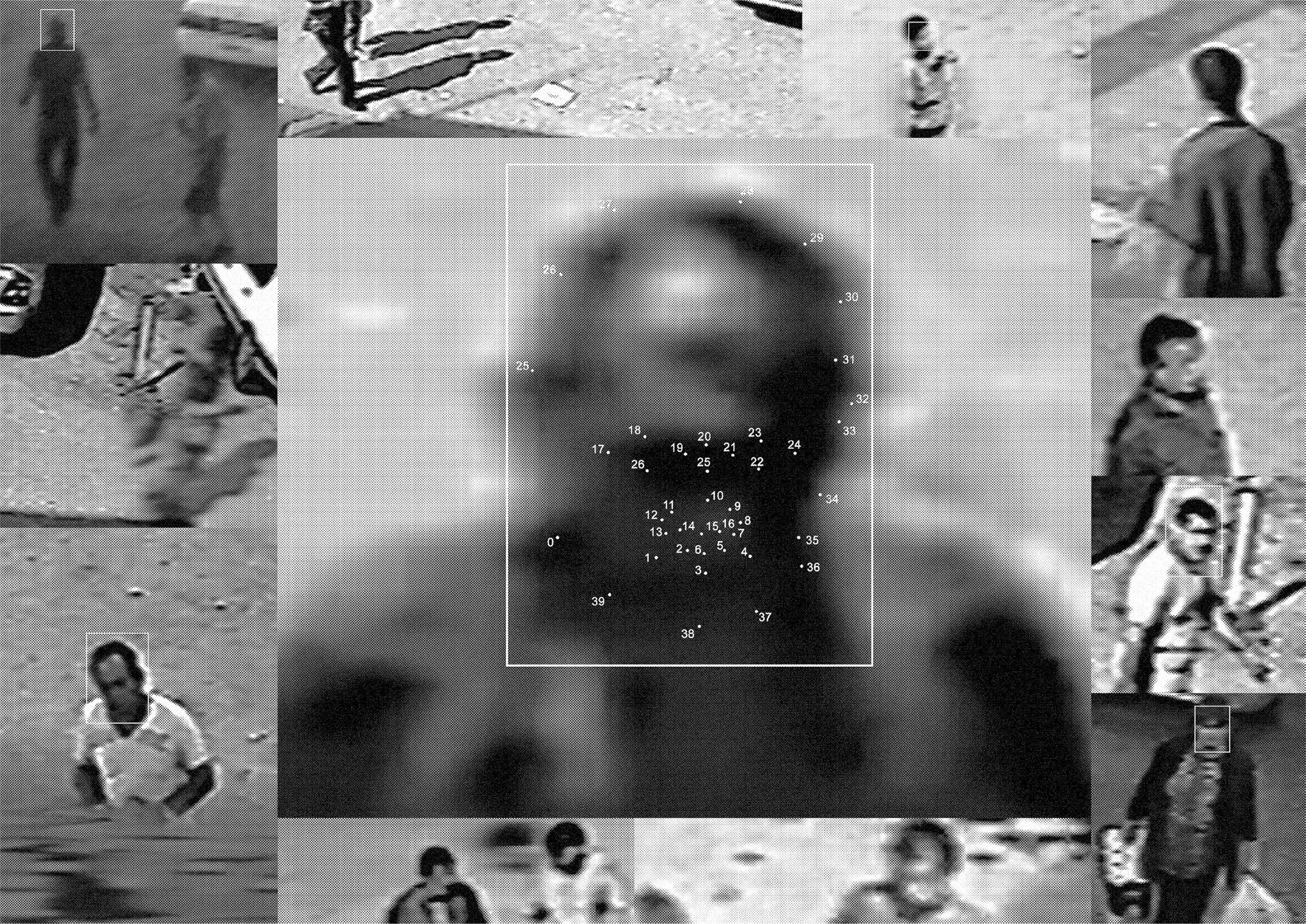

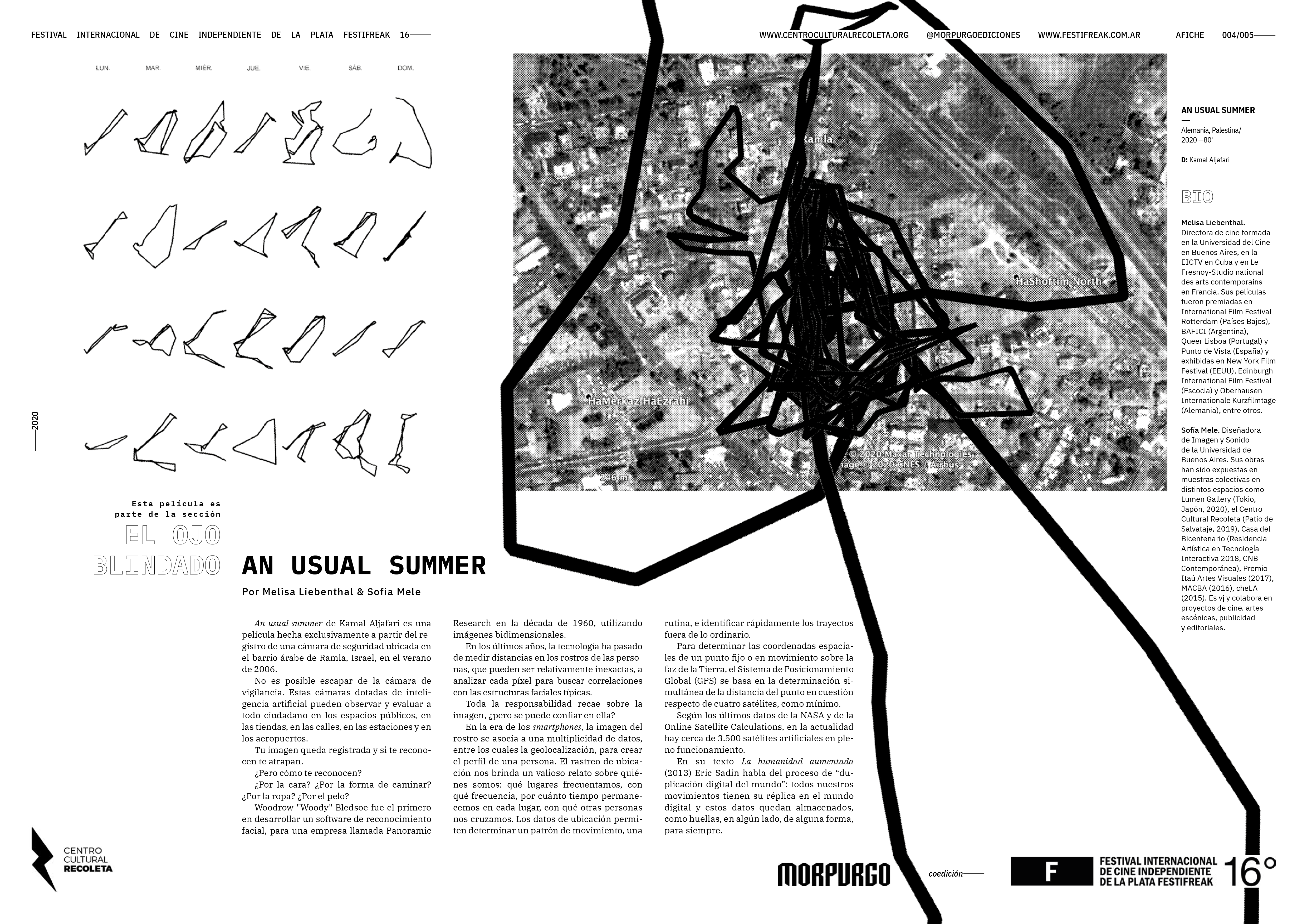

05

FestiFreak Film Festival

¿QUIÉN ARROJÓ LA PIEDRA?

2020

SINOPSIS

Melisa Liebenthal, Sofía Mele (2020, 4’)

Un ensayo audiovisual sobre An Unusual Summer de Kamal Aljafari (Palestina, Alemania, 2020)

An Unusual Summer de Kamal Aljafari es una película hecha exclusivamente a partir de los registros de una cámara de seguridad ubicada en el barrio árabe de Ramla (también conocido como “el Ghetto”), Israel, durante el verano de 2006. Una cámara de vigilancia está dotada de inteligencia artificial y sirve tanto para prevenir delitos como para identificar culpables. La imagen de una persona queda registrada y si la reconocen la atrapan. ¿Pero cómo la reconocen? ¿Por la cara? ¿Por la forma de caminar? ¿Por la ropa? ¿Por el pelo? Toda la responsabilidad recae sobre la imagen, ¿pero se puede confiar en ella?

︎︎︎Melisa Liebenthal and Sofía Mele, FestiFreak Film Festival

Melisa Liebenthal, Sofía Mele (2020, 4’)

Un ensayo audiovisual sobre An Unusual Summer de Kamal Aljafari (Palestina, Alemania, 2020)

An Unusual Summer de Kamal Aljafari es una película hecha exclusivamente a partir de los registros de una cámara de seguridad ubicada en el barrio árabe de Ramla (también conocido como “el Ghetto”), Israel, durante el verano de 2006. Una cámara de vigilancia está dotada de inteligencia artificial y sirve tanto para prevenir delitos como para identificar culpables. La imagen de una persona queda registrada y si la reconocen la atrapan. ¿Pero cómo la reconocen? ¿Por la cara? ¿Por la forma de caminar? ¿Por la ropa? ¿Por el pelo? Toda la responsabilidad recae sobre la imagen, ¿pero se puede confiar en ella?

︎︎︎Melisa Liebenthal and Sofía Mele, FestiFreak Film Festival

04

MnArtists, Walker Art Center

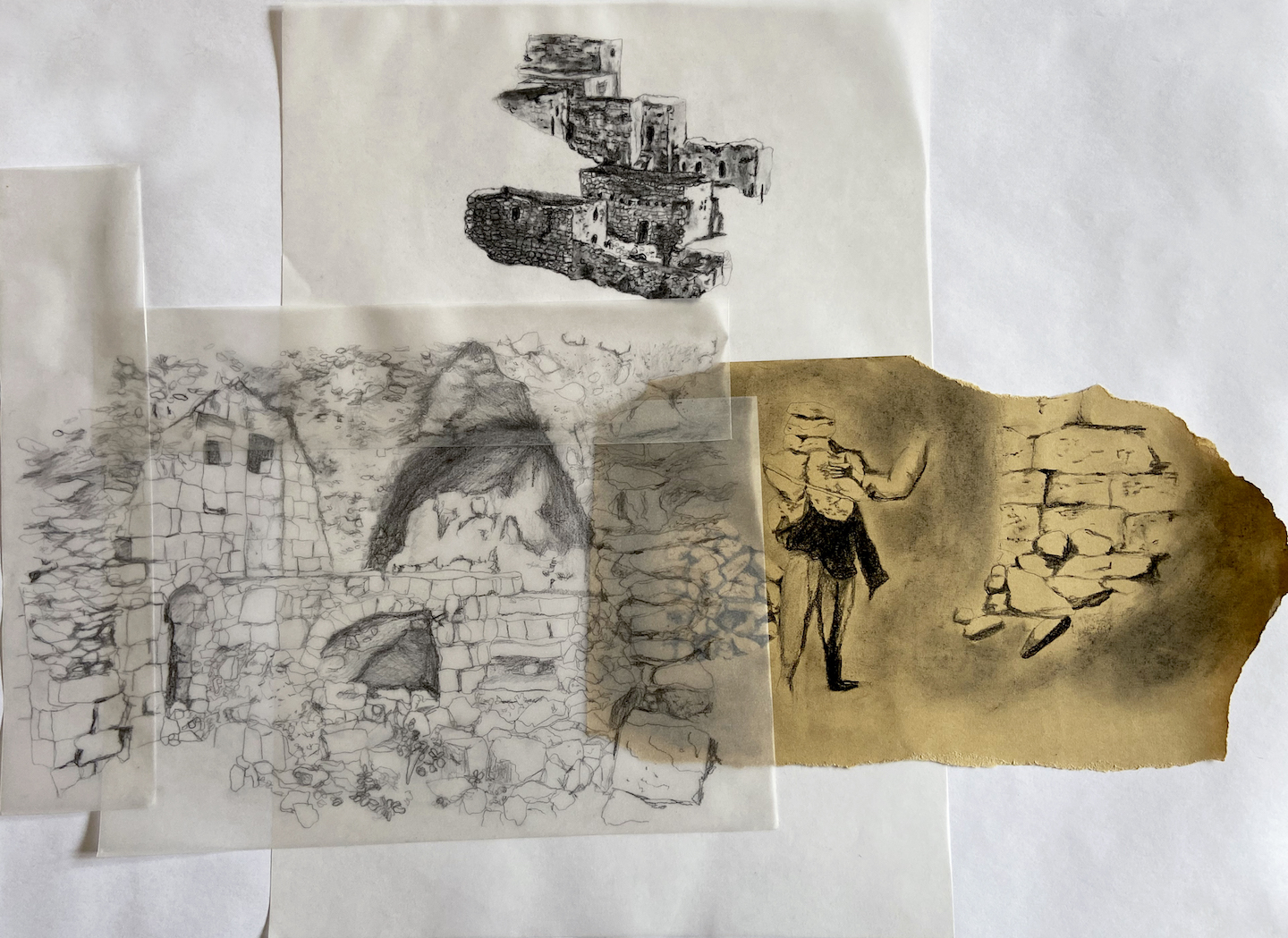

The Silent Chorus of Limestone: Non-human Witnesses to Intimacy, Creation, and Destruction in Settler Colonialism

October 04th 2020

Interdisciplinary artist Lamia Abukhadra delivers a meditation on settler colonial violence that cuts between multiple perspectives—giving voice to limestone “witness stones” as a temporary archive, material witness, and intimate participant in the creation and destruction of Palestinian life.

Read the full writing here: ︎︎︎The Silent Chorus of Limestone: Non-human Witnesses to Intimacy, Creation, and Destruction in Settler Colonialism

︎︎︎Lamia Abukhadra

︎︎︎The Silent Chorus of Limestone – Mn Artists

Read the full writing here: ︎︎︎The Silent Chorus of Limestone: Non-human Witnesses to Intimacy, Creation, and Destruction in Settler Colonialism

︎︎︎Lamia Abukhadra

︎︎︎The Silent Chorus of Limestone – Mn Artists

03

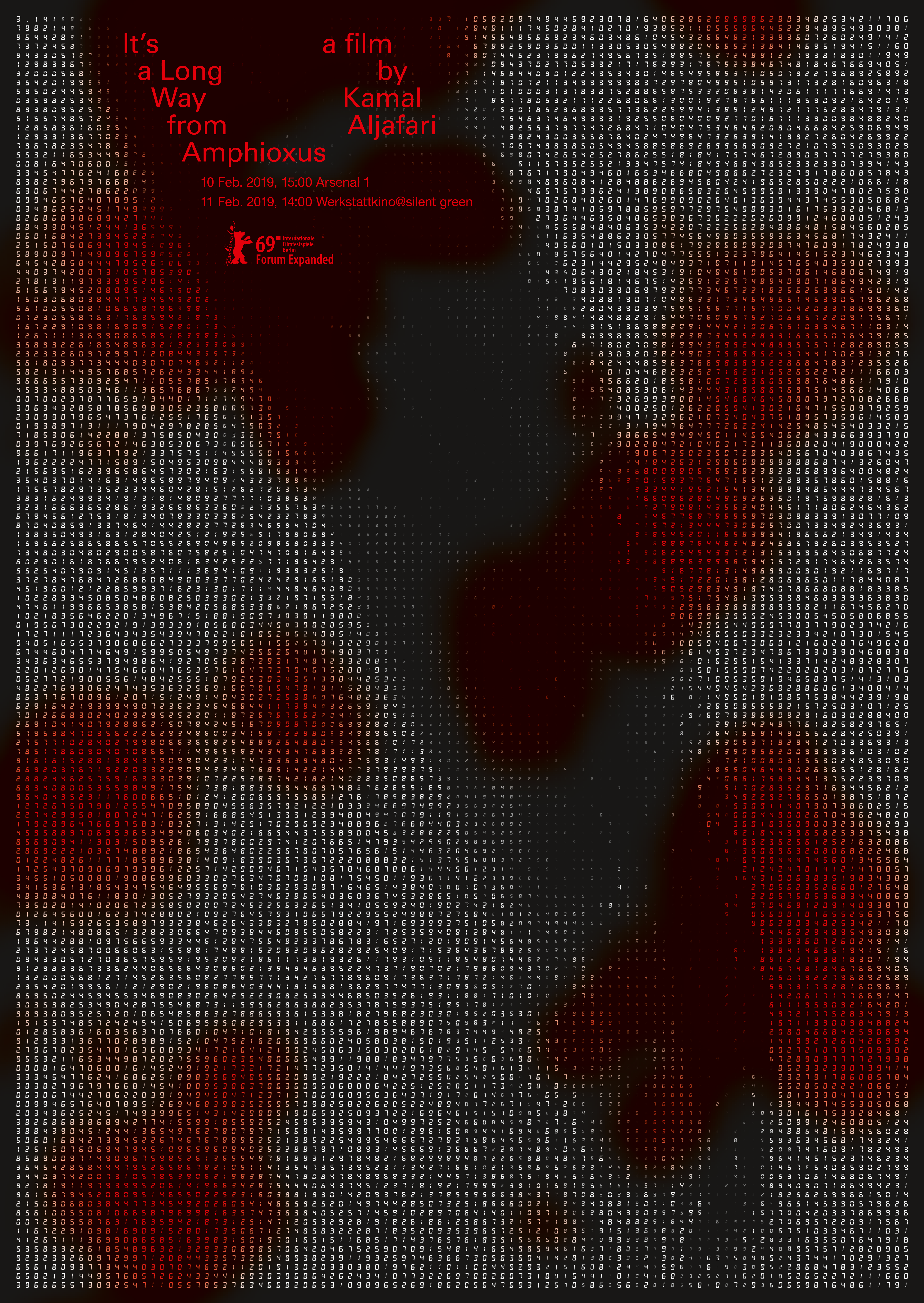

69° Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin

IT’S A LONG WAY FROM AMPHIOXUS, POSTER

2019

Poster designed by Dokho Shin for Kamal Aljafari in occasion of the presentation of his It’s a Long Way From Amphioxus at the 69° Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin, Forum Expanded.

︎︎︎It’s a Long Way From Amphioxus, Forum Expanded – Berlinale

︎︎︎It’s a Long Way From Amphioxus, Forum Expanded – Berlinale

02

MFA STUDIO ARTS –– Concordia University

RECOLLECTION, POSTER

January 28th 2016

“Kamal Aljafari is the chronicler of the inchronicable, visionary of the faded out. Somewhere between the early Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí (“Un Chien Andalou”) and the late Mani Kaul’s entire magnificent oeuvre, in his new film, “Recollection,” Kamal Aljafari has tapped on a disquieting vision of the ruins and debris in material and memorial, pushing as he does his previous work forward by leaps and bounds. The significance of this work is manifold, achieving two contradictory tasks in particular: dismounting the omniscient camera and staging the relic. By allowing the memory to stage and announce itself, an enduring philosophical task made essential as early as in Walter Benjamin’s prophetic turn to relics and ruins in his theory of allegory, Aljafari wonders: who is watching, who is watching the watcher, and by what authority: The damning question: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?: is here staged with astonishing confidence and ease, with the threadbare power of a visionary artist taking the instrumentality of his own art to task. The result is uncanny: You feel you have been there: but where, when, how, and now what?”

–– Hamid Dabashi, Columbia University, New York

︎︎︎MFA Studio Arts, Concordia University

︎︎︎Conversations in Contemporary Art

–– Hamid Dabashi, Columbia University, New York

︎︎︎MFA Studio Arts, Concordia University

︎︎︎Conversations in Contemporary Art

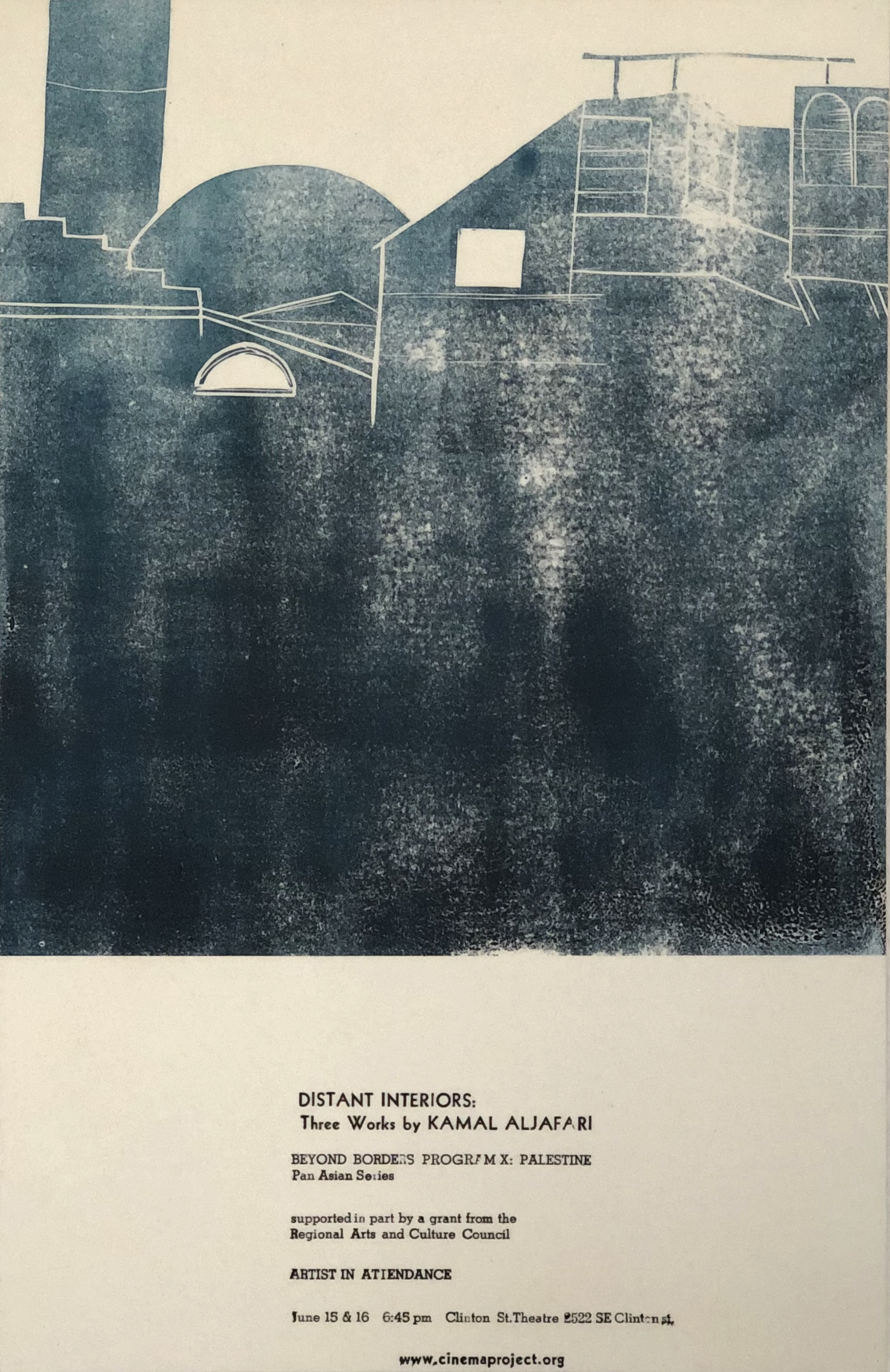

01

Cinema Project, Portland

DISTANT INTERIORS, POSTER

June 15th and 16th 2010

Cinema Project's Pan Asian series of visiting artists is rounded out this season with Palestinian-born independent filmmaker Kamal Aljafari. Through his witty, restrained, and personal documentary style, Aljafari examines varying definitions of home and place in the Middle East. In pieces like The Roof and Port of Memory the focus is primarily on the veritable ghost-town of Jaffa that in pre-1948 Palestine was a thriving urban and economic port-city. These works demonstrate Aljafari's thoughtful but not overly formal compositions of half-inhabited houses and damaged neighborhoods, which reveal the strained co-existence of past and present and the complicated layers of history that help construct (physically and psychologically) such places. Curator Jean-Pierre Rehm has called The Roof "as much a stylistic as a political manifesto." With an approach recalling the suspended action of other international cineastes like Taiwanese Tsai-Ming Liang, Aljafari brings something less mysterious but more palpable to his coded landscapes and personal portraits.

︎︎︎Distant Interiors, Cinema Project

︎︎︎Distant Interiors, Cinema Project