February 18th 2016

Interview

ENGLISH

Kamal Aljafari: Unfinished Balconies in the Sea

Filmmaker Kamal Aljafari talks to Nathalie Handal about the poetry of memory, and displacement in Palestine.

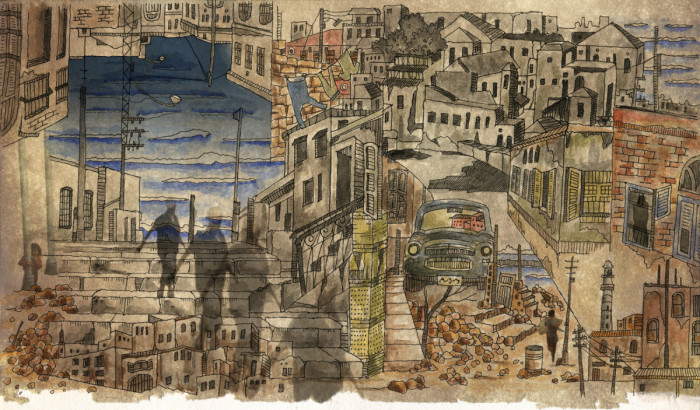

In Kamal Aljafari’s new film Recollection, freedom is experienced in “the sound of the ocean…the echo you can hear outside but recorded from inside the wall. Life buried beneath, inside the sea.” As the images move slowly, other times brusquely, from a silhouette to a shadow, a sliver of the port city of Jaffa to another, the sound moves us into the present unearthing a past. We begin to see the ruins as breathing bodies. We see the place Palestinians have lived in and have been exiled from. And gradually we are brought face-to-face with history, with destruction. The phantoms stare at us. The filmmaker “frees the image,” an act he calls “cinematic justice.”

Recollection is epic. In an impeccable pas de deux between what’s seen and unseen, the Palestinian filmmaker creates a symphonic visual experience. He dives into the crevices of memory, inquires violence, observes stillness.

The film displays the ferocity of occupation and how it’s transfigured in Israeli culture, and in this case more specifically, the cinematic one. To make the film, Aljafari watched every Israeli film shot between the 1960s and 1990s, the majority of which excluded Palestinians. They were, as he affectingly says, “uprooted in reality and in fiction,” explaining that these films used Jaffa because it provided them with “history and narrative.” His film is a witness. In Recollection, he “removed the Israeli actors and gave the stage and space to the people unintentionally filmed in the background [Palestinians].” He says, “I could have worked years on it, not only because I enjoyed removing the actors but because I felt I was doing something magical, that’s only possible in cinema.” The film is visceral, and makes us question what torments a man without a country.

Aljafari was born in al-Ramla, and raised in Jaffa, where his mother is from. The city plays center stage in his three films, which have received numerous awards and accolades for their artistry. Recollection has garnered praise around the globe from Argentina to Torino. Film expert and Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University writes that Kamal Aljafari is a “visionary artist…the chronicler of the inchronicable.” The Argentinian film critic Luciano Monteagudo lauds: “It is very rare to find in today’s cinema a film so original in its conception, so personal in its political commitment, and so inventive in form as Recollection.”

Like the Italian cinema masters Pier Paolo Pasolini and Michelangelo Antonioni, Aljafari’s films challenge our perceptions, transport us to poetic realms and move us. They encompass image and sound crafted with precision. His cinematic language is one built on the alphabet of the sea and its ruins, dream-like ricochets, where silence is storm and soliloquy. Stillness sculpts the complexities of what’s split in displacement and exile, memory and the heart.

If “Jaffa is the sea,” Kamal Aljafari is its waves. I’m reminded of that when we leave Zazza, a café on Schonleinstrasse in the Kreuzberg neighborhood of Berlin, where the interview is conducted. As we walk towards a small bridge, accompanied by the metallic winter skies. Reach the frozen canal, see a few hovering birds. The sea nowhere, the sun absent. I wonder how a filmmaker deeply rooted in a Mediterranean city survives the interminable opaque clouds. When I turn to ask him, I realize wherever he is, Jaffa is present.

After seeing Recollection, viewers want to go back and experience the images again, walk through them, rediscover them, listen to them more judiciously, look at them more deeply, feel them more intensely. Images that amplify our sense of what it means to exist, and what it means to see and be seen.

![]()

G The allegorical opening scene of your new film Recollection, establishes the pulse of the film. The sudden disappearance of people in motion—walking, dancing, running—ending with the shot of a young woman with a white scarf heading to the sea before she vanishes. Is disappearance an act of reemergence?

KA I made a trailer where I wanted to show how this film was made. After the film premiere in the Festival del film Locarno, I thought I should begin the film this way. Removing the actors and zooming in on the figures I found in the background, these ghosts, who never left. Imagine, I was watching these films and in one of them, I saw my uncle walking in the background of a scene. I would see my uncle only from time to time because he was kept in a mental hospital. Seeing him created a moment of reemergence. It is symbolic and natural at the same time, as I only knew him as an outcast ghost. And he haphazardly appears in an Israeli film. We will never know who the young woman vanishing is.

G Is reality in-between what’s visible and invisible?

KA I don’t know about reality. This film shows how there is no difference between reality, fiction, and fantasy. What I found in this material is quite incredible. To have found all these characters who never existed, but were always there. It’s the magic of cinema. It’s beyond our control, it captures everything. The traces are everywhere, traces of the city, the people who inhabited the city, like the face that I found engraved in one of the corners of the windows. In the film, as the main character walks the city, he sees the engraved face on the stone, the first sign of life. He slowly discovers more signs, and collects everything he finds. There is an archeologist inside me.

G The walks are singular and collective and eventually interlace. Can you expand?

KA In the Israeli films, the characters walk on one street that leads to another that isn’t actually adjoining. These filmmakers only cared about the textures of the old city, the photogenic quality of Jaffa. For someone who comes from and knows this place, these films do not make sense. It was important for me to have the character in my film walk and make sense of all of it, and project the place as it is, streets that lead to other streets as they are. How to make a film with all of this? Where to start? Where to walk? The character in Recollection arrives from the sea. The dream of any Palestinian is to arrive from the sea and not the airport to the city, to arrive with no borders. So he arrives to the port and walks up the stairs to one neighborhood, and from there goes to Ajami then al-Manshiyya (the part in black and white). He is able to go everywhere that he isn’t able to go anymore. His walk is his grandfather’s, his mother’s, his uncle’s walk. The walk of all the phantoms he is finding.

G Is that why you use I and him (referring to the main character), interchangeably? It’s a reflection of how the personal is collective?

KA The character filming is many people. The “I” is less a subject than a vehicle, he doesn’t develop, he simply moves and usually on foot, slyly, frequently returning to his point of departure. The “I” is all the ghosts in the film.

G By preserving the mystery in the film, what are you conveying about what has been taken?

KA The character in the movie who films is essential to the act of reclaiming. For me it is reclaiming cinematic territory that was taken away from us. We couldn’t make these films because our society was completely destroyed. What was left behind in Jaffa after 1948 was an insolated, depressed, and poor minority. My family lost all their properties. They were destroyed, bombed, or taken away. We all had to start from zero. My film is trying to correct that in a way—what I call cinematic justice—by giving me the ability to walk and make a film. The character is a photographer. He is filming in a way the Israelis hadn’t filmed there because they didn’t want to see Jaffa. It was meaningless to them and the films they made are the proof. All they wanted was to use Jaffa for the sake of inventing a historical narrative.

My character’s position is different. He knows every corner. Every stone has meaning to him. He sat there, his grandfather sat there. When he touches the stone with his camera, it is emotional for him. It is not a stylistic choice. His camera expresses the sentiments he has. He feels a huge responsibility. He wants to film everything nonstop.

G Why did you film so many close-ups of the walls?

KA The walls witnessed everything. They were left behind, half destroyed. But even if everyone was gone and the city was empty, the people would still be engraved on the walls.

G You are an inquisitor. Memory is thus far your greatest exploration. What have you discovered while meditating on memory?

KA I cannot separate myself from the fact that I live abroad. When I go back to Jaffa, I return to the place I’m from, searching for my memories, that of my family, and the people I love. I search for the city that doesn’t belong to me anymore but that I know is mine. It’s a very schizophrenic feeling. It might be that even if I didn’t go abroad, I would still have made the same movies because I remember always carrying memories of the city. In my childhood, coming back from school to my family house, I saw an Israeli man erasing the name of the Palestinian family who owned the house. This remains in my mind. Every time I walk by this street, I still see traces of the name.

When I work on a film, I have no strategy, it’s something that I feel in the moment, and I go with it. In Recollection, the character has endless memories. He is all of the people we find. And Jaffa is endless. The amount of memory and history there goes beyond any occupation. He is memory itself filming.

G In Federico Garcia Lorca’s “Gacela of Love’s Memory,” he writes, “Don’t carry your memory off. Leave it alone in my heart.” By exploring memory, are you also trying to place it somewhere?

KA I collect because these places are vanishing. I know I’m the only one and last one to do this work. I have to do it. But at the same time, the images have to stay free. Aren’t memories made of images? That’s the power images have over us.

The image with the car: I recognize the corner where I used to sit with my grandfather. I liked to rub by back against the sandstones, typical of house corners in Jaffa. Then my mother told me that this was the car of a relative who was a taxi driver, and this relative had a brother in Lebanon. But I showed it to someone else and he told me that the blue windows are of the house of the Habash family. I realized I couldn’t intervene. I had to leave it. Preserving what it was is difficult, as is not clarifying the meaning of the images for someone who is not from there. In Stockholm someone saw the film and told me, “This is a Ford Anglia,” and added, “I loved that car.” He had a memory with that car. It’s the universality of cinema. A film does not have to be translated.

G Recollection is an emotional experience as much as it is visual and audio, was there a more important facet for you to seize? Robert Bresson said about A Man Escaped, that in his film “freedom is presented by the sounds of life outside.” How is freedom presented in Recollection?

KA The life inside. The sound of the ocean. While recording we used special microphones that could record the sound inside the wall. It was the echo of what you could hear outside but recorded from inside the wall. We also put microphones deep in the water and on the port, to listen to the sound there. The inside sound that we usually don’t hear. It was important for me to listen to the sound of the walls, life buried beneath, inside the sea. The Israeli government and the municipality of Tel Aviv destroyed Jaffa. They threw the homes they destroyed into the sea. But every year, in the winter, when the sea rises, it throws part of these homes back on to the shore. The Tel Aviv municipality collects them, throws them back but the ruins return. Every year the sea brings them back.

We recorded at night because that’s when places free themselves from the present, and its occupiers. There is a shop, which now belongs to an Israeli, but still has the name of the person who owned it, a Palestinian. At night, I’d walk by and see his name. I was interested in capturing the sound of the shop when it was alone, when it went back to being itself.

The same with recording, hearing, listening to the sound of the walls, and the sounds inside the walls. And obviously, the ocean which is the symbol of desire. It comes back. Uncontrollable. It takes over everything.

G Noise, music, silence—why did you include that brief conversation that poignantly ends with the question, “She lives here?” in a film without dialogue?

KA We recorded mostly at night but one day we walked through the city and recorded people. We were in Ajami and there was this girl, maybe eight years old, who was hanging the laundry. She was curious. Looking at us recording sound. She started playing with her balloon and kicking it towards us, trying to play with us, trying to communicate with us. We gave her the mic, and she was very happy. I asked her, “What is your name?” She said, “Yara.” I asked her, “Where do you live?” She told me, “Nahal Oz.” I was surprised, so asked her if it was in Tel Aviv. She said, “No.” I said, “In Jaffa?” She didn’t answer. Then I asked her what she was doing here. And she said she was visiting her grandmother. I asked her grandmother’s name?” She responded, “Sumaia.” I said, “She lives here?” And she didn’t answer.

G Because it is impossible for her to live in Nahal Oz as it’s a settlement.

KA Exactly, it’s a kibbutz settlement at the border of Gaza. And besides, her name is Yara. It’s one of the most Palestinian names you can have. She couldn’t have lived there. It stays a mystery. And cinema should be mysterious.

I think in the future, I will just speak to children. They are unfiltered. She expressed everything I wanted to express and everything the character in the film is feeling. He is from this place but he is not. He is inside but he is outside. He is in Jaffa but he is not. He is visiting family but doesn’t know if they are still here.

G Your films are acquiescent of stillness. What is stillness to you?

KA It is the dream we are all in. In the film, he is walking step by step. Enjoying every moment in the space because it is impossible that he is there. Like in a dream you visit different places, move from one place to another. Which is also like memory. Different places coexist. Different times coexist.

G In the movie Shi (Poetry), the South Korean director Chang-dong Lee dives into the spheres of memory and the importance of seeing the world deeply. Can you tell us what “seeing deeply” means to you?

KA It is an act of spending time – filming a place for a long time to be able to see it. Again, I think it is related to memory. You cannot remember quickly. You need to sit and stare. That is what my camera language is doing. It is contemplating. Among the ancient Greeks, poetry was the mother of all muses. They believed memory was most closely associated to the practice of poetry. The language of the film is the only language that is possible, that of staying. When you write a poem, it is not scripted. This film was made the same way.

G You work with non-actors. Do you think that’s a way to arrive closer to truth?

KA I don’t think it was by choice. I found myself interested in what I found in my family house. The way my aunt was making the bed, so elegant, so original. It somehow expressed everything about her, who she is. No actor can reenact her making the bed the way she was making it. To me, that’s cinema, to capture that poetry. I am not against actors. But I was interested in the give and take relationship that I found in my subjects. I could find it only with people and places that mean so much to me, who I know, who I have feelings for. It is not just acting; It’s about being oneself. They are like that flower or that stone that no one paid attention to.

G What directions, if any, do you give your non-actors or personages?

KA The two rules I follow are never to ask them to do anything they don’t usually do and never to tell them how to do anything. I was interested in capturing feelings and not in directing characters.

G How challenging was it to work with family members?

KA It can be difficult but also quite amazing because there is something so familiar yet new when filming them, when capturing them on camera, which is worth it. Now when I look at the films, I look at family albums.

G What comes to mind when you hear: Youth, early 1980s?

KA One Sunday evening when I was ten or eleven, I was with my sisters watching a film at the Christian Orthodox Club Scouts near my grandmother’s house, and my uncle whispered to me that it was time to go to al-Ramla, where we lived. I didn’t want to go. I wanted to stay in Jaffa. The difference between the two is that my grandparents were in Jaffa. And Jaffa had this strong feeling of left over urban society that attracted me, that I felt comfortable with, that I saw my self in. I can still feel Jaffa’s cosmopolitan past in the way people talk and walk, the way people live, the sea.

G What comes to mind when you hear: Intifada 1987?

KA I was in Terra Santa High School in Jaffa at the time, and watching the images on television with my family at night—Palestinians in the streets, soldiers breaking the arms of young people—made me increasingly political. Against the will of my parents, I started reading the newspaper of the communist party. My father told the old man from the neighborhood Abu Nijem (Nijm means star in Arabic, and was the name of his oldest son), who brought me the newspaper, not to bring it anymore. He paid him the yearly membership I asked for. He didn’t want me involved in politics. In a way my father was right. He told me, “When I was your age, I walked ten kilometers with my friends to watch the only television in Lydd to listen to Nasser [Gamal Abdel Nasser]. But in the end, we got nothing from all of that.” Of course as a young man, I felt strong. I didn’t want to listen to such stories. I would go to Nazareth to take part in demonstrations and I would come back at two in the morning and my father would not open the door for me.

G How is the Jaffa of today different from the Jaffa of your childhood?

KA In a way it’s worse. There were remains when I grew up. There were some ruins. But in the last fifteen years, with the gentrification project taking place in Jaffa, more has disappeared. They take old Palestinian houses, renovate them, change their identity. Sometimes it’s worse to change the identity to the point where you can’t recognize it anymore than to destroy the house. Gentrification, and in this case there is a political meaning to it, makes you feel not at home in your home. If I walk now in the streets where my grandparents have lived most of their lives, I feel lost and displaced. This erasure is painful. Of course, I never forget that this is where I am from.

G What remains intact for you?

KA here is a feeling. It’s in the air, in the smell of the place. The wind coming from the ocean, which somehow keeps these endless memories that I am speaking about. It’s the smell of people who are no longer there.

G What was it like growing up Palestinian in Israel? Being excluded—metaphorically, physically, emotionally—from the place you are from?

KA The most painful thing is that you are made to feel like an immigrant in your own country. That’s the feeling I had. On one side I knew, I know, that I’m from there, but on the other hand, I didn’t feel comfortable to be myself. I had to hide my identity. I had to speak a language that was not mine. I had to speak Hebrew. And as a child I was always worried to be asked my name. My name would reveal my identity. Your existence is in question all the time. Surely, when you grow up, you resist that and say your name without being afraid. But as a child, you go to the swimming pool and are forced to pretend you are someone else to protect yourself and be like the other children. Palestinian society was completely uprooted and those of us who stayed were isolated, left alone, and had to deal with the situation, had to survive it the best way we could. When a child hides his/her identity it is an act of survival, as he/she feels discriminated against. When I went abroad, my state of mind never changed. I’ve always felt like an immigrant.

G Identity is a topic that constantly surfaces. Is identity an illusion, a boundary?

KA We are many things. In the case of Palestinian identity, I find it diverse and rich, and in a way unnationalistic despite all. There is something impressive about that, because this is a nation that’s been under occupation, you expect them to be more nationalistic, but they are not. It’s actually the occupiers who are nationalistic. I feel Palestinian identity has no borders.

G Departures and arrivals to and from Jaffa today—what is the journey like for you each time?

KA I carry an Israeli passport but I can’t help feel that they might not let me in. It is very strange as I am from there. I can’t help worry the moment I arrive at passport control. I never know if I will go in or not. That’s the feeling I have each time. It is the mental terror we all live in generation after generation.

Now I have the image of opening the door at my grandparents’ house, which is always unlocked. There is something beautiful about that feeling, that when you arrive, you can just open the door. The last time I went, I wanted to stay.

G How about time—Palestinians seem to live outside of time. What do you think of what Juan Goytisolo in the novel Exiled From Almost Everywhere writes: “Everything runs its course, including time itself.”

KA In relation to memory, time is beyond me. That’s how the film was made, in relationship to time. Being in all times. That said, at this moment, Palestinians remain outsiders. Maybe now it is more comfortable to be Palestinian in some places. But coming from this unresolved cause, which probably won’t be solved in the next years, we remain outsiders. As a filmmaker, I am at the edge of time. Being at the edge is the right position in relation to these players, and from which to look at the world.

G You live in Germany. There is an influx of refugees including Palestinians from Yarmouk refugee camp in Syria, Many make that difficult journey across the sea. Your family stayed in Jaffa because the sea was turbulent and brought them back. What is your experience with these recent refugees?

KA I’ve met many of them and have listened to their stories of fleeing Yarmouk. In a way, while in Yarmouk they copied what they lost in Palestine, and lived “outside of time” in that sense. But this reproduced space, once again, was completely destroyed. Many of them lost friends, family members died at sea. They carry this feeling of being multiply dispossessed. This experience made them more Palestinian than before. It is interesting to observe how strong and preserved their Palestinian identity is, despite everything. They physically lived the experience of their grandparents who had to flee in 1948.

There is a neighborhood in Berlin—Neukölln—where the refugees go to eat because there are many Arabic restaurants. The arrival of this huge number of refugees is becoming a counterattack against the hipsters who were coming to the area. I like that. They fill the place with life. And obviously, I am happy to hear the Arabic language and walk among them.

G You studied theatre and wrote your thesis on Lorca’s play Blood Wedding. Has Lorca informed you as a filmmaker?

KA I ended up in the theatre department by chance. Being at Hebrew University, the Israelis I met in this department were pleasant people in comparison with the Israelis who were studying history, as I had originally been studying too. In theatre, the atmosphere was freer, less tense. I discovered Lorca, and his world and metaphors were mine. In “Romance Sonámbulo,” he wrote, “But now I am not I, nor is my house now my house. Let me climb up, at least, up to the high balconies.” His high balconies reminded me of where I come from, a place with unfinished balconies. Lorca’s emotions and metaphors spoke to me. I felt Lorca came from where I come from. And I discovered Blood Wedding, which is an amazing theatre piece, and the film adaption of the play by Carlos Saura, which moved me. The flamenco dancer Antonio Gades, while putting on his make up, talks to the camera about his experience living in Paris in an apartment that he later discovered was the same one his master from Spain lived in years before. The mysterious feelings the film evoked spoke to me. I remember that moment well as it was the year I saw the film Chronicle of Disappearance (1996) by the Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman, a milestone in world cinema.

G Is there an approach that you are interested in exploring?

KA I want these ghosts to reach out more, be more visible, talk, even dance. I would like to take the aesthetic and visual language I developed to another level. A film that will reach more people, and allow me to explore places I haven’t before, cinematically speaking.

G You’ve also exhibited your photographs, most recently at the Beirut Art Center, and are working on a book?

KA I want to continue the conversation I began on screen in print. The book is an album of the city and people, a memory in images rescued from the screen of dozens of Israeli fiction films shot in Jaffa as early as the 1960s.

G You also lived in the US. You were the Benjamin White Whitney fellow at Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute and Film Study Center in 2009-2010, and taught film at The New School in New York in 2010, before returning to Germany to become a senior lecturer and program director of the German Film And Television Academy in Berlin, 2011-2013. Can you speak about your time in New York City.

KA New York City is the only place I lived in where I felt I could stay. I never felt that in any other place. I always have a feeling I should move on to somewhere else. Having people like myself coming from all over the world, all having accents, makes me feel comfortable. And it’s a city you feel you have been to before even when you haven’t, because of cinema. Whether this feeling is true or an illusion, I don’t know. But that’s how I felt in NYC.

G Being exiled, are you rooted in the absence of place or do you carry place with you?

KA I carry place with me. But it’s paradoxical because there is a certain absence in it as well. Perhaps it’s my autobiography, the places I came from—the unfinished second floor of my parents’ house, my grandparent’s house previously belonging to Palestinian Armenians, which my family was forced to live in after they lost their house in the al-Manshiyya neighborhood. There is always an absence even in the place I am carrying with me. Once, when I was a child I asked my father to take me to the house where he was born. We walked to an empty neighborhood, there was nothing where his house stood.

G So is memory home? Or in searching for what’s lost, has cinema become home?

KA Cinema more and more. I realize that I can inhabit these places only in the movies I am making.

G At the end of Recollection, a certain freedom is projected, images of people. Can you speak about that scene?

KA I love that scene because it is so hopeful. These phantoms are walking together, hand in hand. They are singing. It is a song where they are declaring themselves. They decide to walk and sing and talk to the world. It’s a final march where these ghosts are no longer ghosts.

In Kamal Aljafari’s new film Recollection, freedom is experienced in “the sound of the ocean…the echo you can hear outside but recorded from inside the wall. Life buried beneath, inside the sea.” As the images move slowly, other times brusquely, from a silhouette to a shadow, a sliver of the port city of Jaffa to another, the sound moves us into the present unearthing a past. We begin to see the ruins as breathing bodies. We see the place Palestinians have lived in and have been exiled from. And gradually we are brought face-to-face with history, with destruction. The phantoms stare at us. The filmmaker “frees the image,” an act he calls “cinematic justice.”

Recollection is epic. In an impeccable pas de deux between what’s seen and unseen, the Palestinian filmmaker creates a symphonic visual experience. He dives into the crevices of memory, inquires violence, observes stillness.

The film displays the ferocity of occupation and how it’s transfigured in Israeli culture, and in this case more specifically, the cinematic one. To make the film, Aljafari watched every Israeli film shot between the 1960s and 1990s, the majority of which excluded Palestinians. They were, as he affectingly says, “uprooted in reality and in fiction,” explaining that these films used Jaffa because it provided them with “history and narrative.” His film is a witness. In Recollection, he “removed the Israeli actors and gave the stage and space to the people unintentionally filmed in the background [Palestinians].” He says, “I could have worked years on it, not only because I enjoyed removing the actors but because I felt I was doing something magical, that’s only possible in cinema.” The film is visceral, and makes us question what torments a man without a country.

Aljafari was born in al-Ramla, and raised in Jaffa, where his mother is from. The city plays center stage in his three films, which have received numerous awards and accolades for their artistry. Recollection has garnered praise around the globe from Argentina to Torino. Film expert and Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University writes that Kamal Aljafari is a “visionary artist…the chronicler of the inchronicable.” The Argentinian film critic Luciano Monteagudo lauds: “It is very rare to find in today’s cinema a film so original in its conception, so personal in its political commitment, and so inventive in form as Recollection.”

Like the Italian cinema masters Pier Paolo Pasolini and Michelangelo Antonioni, Aljafari’s films challenge our perceptions, transport us to poetic realms and move us. They encompass image and sound crafted with precision. His cinematic language is one built on the alphabet of the sea and its ruins, dream-like ricochets, where silence is storm and soliloquy. Stillness sculpts the complexities of what’s split in displacement and exile, memory and the heart.

If “Jaffa is the sea,” Kamal Aljafari is its waves. I’m reminded of that when we leave Zazza, a café on Schonleinstrasse in the Kreuzberg neighborhood of Berlin, where the interview is conducted. As we walk towards a small bridge, accompanied by the metallic winter skies. Reach the frozen canal, see a few hovering birds. The sea nowhere, the sun absent. I wonder how a filmmaker deeply rooted in a Mediterranean city survives the interminable opaque clouds. When I turn to ask him, I realize wherever he is, Jaffa is present.

After seeing Recollection, viewers want to go back and experience the images again, walk through them, rediscover them, listen to them more judiciously, look at them more deeply, feel them more intensely. Images that amplify our sense of what it means to exist, and what it means to see and be seen.

G The allegorical opening scene of your new film Recollection, establishes the pulse of the film. The sudden disappearance of people in motion—walking, dancing, running—ending with the shot of a young woman with a white scarf heading to the sea before she vanishes. Is disappearance an act of reemergence?

KA I made a trailer where I wanted to show how this film was made. After the film premiere in the Festival del film Locarno, I thought I should begin the film this way. Removing the actors and zooming in on the figures I found in the background, these ghosts, who never left. Imagine, I was watching these films and in one of them, I saw my uncle walking in the background of a scene. I would see my uncle only from time to time because he was kept in a mental hospital. Seeing him created a moment of reemergence. It is symbolic and natural at the same time, as I only knew him as an outcast ghost. And he haphazardly appears in an Israeli film. We will never know who the young woman vanishing is.

G Is reality in-between what’s visible and invisible?

KA I don’t know about reality. This film shows how there is no difference between reality, fiction, and fantasy. What I found in this material is quite incredible. To have found all these characters who never existed, but were always there. It’s the magic of cinema. It’s beyond our control, it captures everything. The traces are everywhere, traces of the city, the people who inhabited the city, like the face that I found engraved in one of the corners of the windows. In the film, as the main character walks the city, he sees the engraved face on the stone, the first sign of life. He slowly discovers more signs, and collects everything he finds. There is an archeologist inside me.

G The walks are singular and collective and eventually interlace. Can you expand?

KA In the Israeli films, the characters walk on one street that leads to another that isn’t actually adjoining. These filmmakers only cared about the textures of the old city, the photogenic quality of Jaffa. For someone who comes from and knows this place, these films do not make sense. It was important for me to have the character in my film walk and make sense of all of it, and project the place as it is, streets that lead to other streets as they are. How to make a film with all of this? Where to start? Where to walk? The character in Recollection arrives from the sea. The dream of any Palestinian is to arrive from the sea and not the airport to the city, to arrive with no borders. So he arrives to the port and walks up the stairs to one neighborhood, and from there goes to Ajami then al-Manshiyya (the part in black and white). He is able to go everywhere that he isn’t able to go anymore. His walk is his grandfather’s, his mother’s, his uncle’s walk. The walk of all the phantoms he is finding.

G Is that why you use I and him (referring to the main character), interchangeably? It’s a reflection of how the personal is collective?

KA The character filming is many people. The “I” is less a subject than a vehicle, he doesn’t develop, he simply moves and usually on foot, slyly, frequently returning to his point of departure. The “I” is all the ghosts in the film.

G By preserving the mystery in the film, what are you conveying about what has been taken?

KA The character in the movie who films is essential to the act of reclaiming. For me it is reclaiming cinematic territory that was taken away from us. We couldn’t make these films because our society was completely destroyed. What was left behind in Jaffa after 1948 was an insolated, depressed, and poor minority. My family lost all their properties. They were destroyed, bombed, or taken away. We all had to start from zero. My film is trying to correct that in a way—what I call cinematic justice—by giving me the ability to walk and make a film. The character is a photographer. He is filming in a way the Israelis hadn’t filmed there because they didn’t want to see Jaffa. It was meaningless to them and the films they made are the proof. All they wanted was to use Jaffa for the sake of inventing a historical narrative.

My character’s position is different. He knows every corner. Every stone has meaning to him. He sat there, his grandfather sat there. When he touches the stone with his camera, it is emotional for him. It is not a stylistic choice. His camera expresses the sentiments he has. He feels a huge responsibility. He wants to film everything nonstop.

G Why did you film so many close-ups of the walls?

KA The walls witnessed everything. They were left behind, half destroyed. But even if everyone was gone and the city was empty, the people would still be engraved on the walls.

G You are an inquisitor. Memory is thus far your greatest exploration. What have you discovered while meditating on memory?

KA I cannot separate myself from the fact that I live abroad. When I go back to Jaffa, I return to the place I’m from, searching for my memories, that of my family, and the people I love. I search for the city that doesn’t belong to me anymore but that I know is mine. It’s a very schizophrenic feeling. It might be that even if I didn’t go abroad, I would still have made the same movies because I remember always carrying memories of the city. In my childhood, coming back from school to my family house, I saw an Israeli man erasing the name of the Palestinian family who owned the house. This remains in my mind. Every time I walk by this street, I still see traces of the name.

When I work on a film, I have no strategy, it’s something that I feel in the moment, and I go with it. In Recollection, the character has endless memories. He is all of the people we find. And Jaffa is endless. The amount of memory and history there goes beyond any occupation. He is memory itself filming.

G In Federico Garcia Lorca’s “Gacela of Love’s Memory,” he writes, “Don’t carry your memory off. Leave it alone in my heart.” By exploring memory, are you also trying to place it somewhere?

KA I collect because these places are vanishing. I know I’m the only one and last one to do this work. I have to do it. But at the same time, the images have to stay free. Aren’t memories made of images? That’s the power images have over us.

The image with the car: I recognize the corner where I used to sit with my grandfather. I liked to rub by back against the sandstones, typical of house corners in Jaffa. Then my mother told me that this was the car of a relative who was a taxi driver, and this relative had a brother in Lebanon. But I showed it to someone else and he told me that the blue windows are of the house of the Habash family. I realized I couldn’t intervene. I had to leave it. Preserving what it was is difficult, as is not clarifying the meaning of the images for someone who is not from there. In Stockholm someone saw the film and told me, “This is a Ford Anglia,” and added, “I loved that car.” He had a memory with that car. It’s the universality of cinema. A film does not have to be translated.

G Recollection is an emotional experience as much as it is visual and audio, was there a more important facet for you to seize? Robert Bresson said about A Man Escaped, that in his film “freedom is presented by the sounds of life outside.” How is freedom presented in Recollection?

KA The life inside. The sound of the ocean. While recording we used special microphones that could record the sound inside the wall. It was the echo of what you could hear outside but recorded from inside the wall. We also put microphones deep in the water and on the port, to listen to the sound there. The inside sound that we usually don’t hear. It was important for me to listen to the sound of the walls, life buried beneath, inside the sea. The Israeli government and the municipality of Tel Aviv destroyed Jaffa. They threw the homes they destroyed into the sea. But every year, in the winter, when the sea rises, it throws part of these homes back on to the shore. The Tel Aviv municipality collects them, throws them back but the ruins return. Every year the sea brings them back.

We recorded at night because that’s when places free themselves from the present, and its occupiers. There is a shop, which now belongs to an Israeli, but still has the name of the person who owned it, a Palestinian. At night, I’d walk by and see his name. I was interested in capturing the sound of the shop when it was alone, when it went back to being itself.

The same with recording, hearing, listening to the sound of the walls, and the sounds inside the walls. And obviously, the ocean which is the symbol of desire. It comes back. Uncontrollable. It takes over everything.

G Noise, music, silence—why did you include that brief conversation that poignantly ends with the question, “She lives here?” in a film without dialogue?

KA We recorded mostly at night but one day we walked through the city and recorded people. We were in Ajami and there was this girl, maybe eight years old, who was hanging the laundry. She was curious. Looking at us recording sound. She started playing with her balloon and kicking it towards us, trying to play with us, trying to communicate with us. We gave her the mic, and she was very happy. I asked her, “What is your name?” She said, “Yara.” I asked her, “Where do you live?” She told me, “Nahal Oz.” I was surprised, so asked her if it was in Tel Aviv. She said, “No.” I said, “In Jaffa?” She didn’t answer. Then I asked her what she was doing here. And she said she was visiting her grandmother. I asked her grandmother’s name?” She responded, “Sumaia.” I said, “She lives here?” And she didn’t answer.

G Because it is impossible for her to live in Nahal Oz as it’s a settlement.

KA Exactly, it’s a kibbutz settlement at the border of Gaza. And besides, her name is Yara. It’s one of the most Palestinian names you can have. She couldn’t have lived there. It stays a mystery. And cinema should be mysterious.

I think in the future, I will just speak to children. They are unfiltered. She expressed everything I wanted to express and everything the character in the film is feeling. He is from this place but he is not. He is inside but he is outside. He is in Jaffa but he is not. He is visiting family but doesn’t know if they are still here.

G Your films are acquiescent of stillness. What is stillness to you?

KA It is the dream we are all in. In the film, he is walking step by step. Enjoying every moment in the space because it is impossible that he is there. Like in a dream you visit different places, move from one place to another. Which is also like memory. Different places coexist. Different times coexist.

G In the movie Shi (Poetry), the South Korean director Chang-dong Lee dives into the spheres of memory and the importance of seeing the world deeply. Can you tell us what “seeing deeply” means to you?

KA It is an act of spending time – filming a place for a long time to be able to see it. Again, I think it is related to memory. You cannot remember quickly. You need to sit and stare. That is what my camera language is doing. It is contemplating. Among the ancient Greeks, poetry was the mother of all muses. They believed memory was most closely associated to the practice of poetry. The language of the film is the only language that is possible, that of staying. When you write a poem, it is not scripted. This film was made the same way.

G You work with non-actors. Do you think that’s a way to arrive closer to truth?

KA I don’t think it was by choice. I found myself interested in what I found in my family house. The way my aunt was making the bed, so elegant, so original. It somehow expressed everything about her, who she is. No actor can reenact her making the bed the way she was making it. To me, that’s cinema, to capture that poetry. I am not against actors. But I was interested in the give and take relationship that I found in my subjects. I could find it only with people and places that mean so much to me, who I know, who I have feelings for. It is not just acting; It’s about being oneself. They are like that flower or that stone that no one paid attention to.

G What directions, if any, do you give your non-actors or personages?

KA The two rules I follow are never to ask them to do anything they don’t usually do and never to tell them how to do anything. I was interested in capturing feelings and not in directing characters.

G How challenging was it to work with family members?

KA It can be difficult but also quite amazing because there is something so familiar yet new when filming them, when capturing them on camera, which is worth it. Now when I look at the films, I look at family albums.

G What comes to mind when you hear: Youth, early 1980s?

KA One Sunday evening when I was ten or eleven, I was with my sisters watching a film at the Christian Orthodox Club Scouts near my grandmother’s house, and my uncle whispered to me that it was time to go to al-Ramla, where we lived. I didn’t want to go. I wanted to stay in Jaffa. The difference between the two is that my grandparents were in Jaffa. And Jaffa had this strong feeling of left over urban society that attracted me, that I felt comfortable with, that I saw my self in. I can still feel Jaffa’s cosmopolitan past in the way people talk and walk, the way people live, the sea.

G What comes to mind when you hear: Intifada 1987?

KA I was in Terra Santa High School in Jaffa at the time, and watching the images on television with my family at night—Palestinians in the streets, soldiers breaking the arms of young people—made me increasingly political. Against the will of my parents, I started reading the newspaper of the communist party. My father told the old man from the neighborhood Abu Nijem (Nijm means star in Arabic, and was the name of his oldest son), who brought me the newspaper, not to bring it anymore. He paid him the yearly membership I asked for. He didn’t want me involved in politics. In a way my father was right. He told me, “When I was your age, I walked ten kilometers with my friends to watch the only television in Lydd to listen to Nasser [Gamal Abdel Nasser]. But in the end, we got nothing from all of that.” Of course as a young man, I felt strong. I didn’t want to listen to such stories. I would go to Nazareth to take part in demonstrations and I would come back at two in the morning and my father would not open the door for me.

G How is the Jaffa of today different from the Jaffa of your childhood?

KA In a way it’s worse. There were remains when I grew up. There were some ruins. But in the last fifteen years, with the gentrification project taking place in Jaffa, more has disappeared. They take old Palestinian houses, renovate them, change their identity. Sometimes it’s worse to change the identity to the point where you can’t recognize it anymore than to destroy the house. Gentrification, and in this case there is a political meaning to it, makes you feel not at home in your home. If I walk now in the streets where my grandparents have lived most of their lives, I feel lost and displaced. This erasure is painful. Of course, I never forget that this is where I am from.

G What remains intact for you?

KA here is a feeling. It’s in the air, in the smell of the place. The wind coming from the ocean, which somehow keeps these endless memories that I am speaking about. It’s the smell of people who are no longer there.

G What was it like growing up Palestinian in Israel? Being excluded—metaphorically, physically, emotionally—from the place you are from?

KA The most painful thing is that you are made to feel like an immigrant in your own country. That’s the feeling I had. On one side I knew, I know, that I’m from there, but on the other hand, I didn’t feel comfortable to be myself. I had to hide my identity. I had to speak a language that was not mine. I had to speak Hebrew. And as a child I was always worried to be asked my name. My name would reveal my identity. Your existence is in question all the time. Surely, when you grow up, you resist that and say your name without being afraid. But as a child, you go to the swimming pool and are forced to pretend you are someone else to protect yourself and be like the other children. Palestinian society was completely uprooted and those of us who stayed were isolated, left alone, and had to deal with the situation, had to survive it the best way we could. When a child hides his/her identity it is an act of survival, as he/she feels discriminated against. When I went abroad, my state of mind never changed. I’ve always felt like an immigrant.

G Identity is a topic that constantly surfaces. Is identity an illusion, a boundary?

KA We are many things. In the case of Palestinian identity, I find it diverse and rich, and in a way unnationalistic despite all. There is something impressive about that, because this is a nation that’s been under occupation, you expect them to be more nationalistic, but they are not. It’s actually the occupiers who are nationalistic. I feel Palestinian identity has no borders.

G Departures and arrivals to and from Jaffa today—what is the journey like for you each time?

KA I carry an Israeli passport but I can’t help feel that they might not let me in. It is very strange as I am from there. I can’t help worry the moment I arrive at passport control. I never know if I will go in or not. That’s the feeling I have each time. It is the mental terror we all live in generation after generation.

Now I have the image of opening the door at my grandparents’ house, which is always unlocked. There is something beautiful about that feeling, that when you arrive, you can just open the door. The last time I went, I wanted to stay.

G How about time—Palestinians seem to live outside of time. What do you think of what Juan Goytisolo in the novel Exiled From Almost Everywhere writes: “Everything runs its course, including time itself.”

KA In relation to memory, time is beyond me. That’s how the film was made, in relationship to time. Being in all times. That said, at this moment, Palestinians remain outsiders. Maybe now it is more comfortable to be Palestinian in some places. But coming from this unresolved cause, which probably won’t be solved in the next years, we remain outsiders. As a filmmaker, I am at the edge of time. Being at the edge is the right position in relation to these players, and from which to look at the world.

G You live in Germany. There is an influx of refugees including Palestinians from Yarmouk refugee camp in Syria, Many make that difficult journey across the sea. Your family stayed in Jaffa because the sea was turbulent and brought them back. What is your experience with these recent refugees?

KA I’ve met many of them and have listened to their stories of fleeing Yarmouk. In a way, while in Yarmouk they copied what they lost in Palestine, and lived “outside of time” in that sense. But this reproduced space, once again, was completely destroyed. Many of them lost friends, family members died at sea. They carry this feeling of being multiply dispossessed. This experience made them more Palestinian than before. It is interesting to observe how strong and preserved their Palestinian identity is, despite everything. They physically lived the experience of their grandparents who had to flee in 1948.

There is a neighborhood in Berlin—Neukölln—where the refugees go to eat because there are many Arabic restaurants. The arrival of this huge number of refugees is becoming a counterattack against the hipsters who were coming to the area. I like that. They fill the place with life. And obviously, I am happy to hear the Arabic language and walk among them.

G You studied theatre and wrote your thesis on Lorca’s play Blood Wedding. Has Lorca informed you as a filmmaker?

KA I ended up in the theatre department by chance. Being at Hebrew University, the Israelis I met in this department were pleasant people in comparison with the Israelis who were studying history, as I had originally been studying too. In theatre, the atmosphere was freer, less tense. I discovered Lorca, and his world and metaphors were mine. In “Romance Sonámbulo,” he wrote, “But now I am not I, nor is my house now my house. Let me climb up, at least, up to the high balconies.” His high balconies reminded me of where I come from, a place with unfinished balconies. Lorca’s emotions and metaphors spoke to me. I felt Lorca came from where I come from. And I discovered Blood Wedding, which is an amazing theatre piece, and the film adaption of the play by Carlos Saura, which moved me. The flamenco dancer Antonio Gades, while putting on his make up, talks to the camera about his experience living in Paris in an apartment that he later discovered was the same one his master from Spain lived in years before. The mysterious feelings the film evoked spoke to me. I remember that moment well as it was the year I saw the film Chronicle of Disappearance (1996) by the Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman, a milestone in world cinema.

G Is there an approach that you are interested in exploring?

KA I want these ghosts to reach out more, be more visible, talk, even dance. I would like to take the aesthetic and visual language I developed to another level. A film that will reach more people, and allow me to explore places I haven’t before, cinematically speaking.

G You’ve also exhibited your photographs, most recently at the Beirut Art Center, and are working on a book?

KA I want to continue the conversation I began on screen in print. The book is an album of the city and people, a memory in images rescued from the screen of dozens of Israeli fiction films shot in Jaffa as early as the 1960s.

G You also lived in the US. You were the Benjamin White Whitney fellow at Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute and Film Study Center in 2009-2010, and taught film at The New School in New York in 2010, before returning to Germany to become a senior lecturer and program director of the German Film And Television Academy in Berlin, 2011-2013. Can you speak about your time in New York City.

KA New York City is the only place I lived in where I felt I could stay. I never felt that in any other place. I always have a feeling I should move on to somewhere else. Having people like myself coming from all over the world, all having accents, makes me feel comfortable. And it’s a city you feel you have been to before even when you haven’t, because of cinema. Whether this feeling is true or an illusion, I don’t know. But that’s how I felt in NYC.

G Being exiled, are you rooted in the absence of place or do you carry place with you?

KA I carry place with me. But it’s paradoxical because there is a certain absence in it as well. Perhaps it’s my autobiography, the places I came from—the unfinished second floor of my parents’ house, my grandparent’s house previously belonging to Palestinian Armenians, which my family was forced to live in after they lost their house in the al-Manshiyya neighborhood. There is always an absence even in the place I am carrying with me. Once, when I was a child I asked my father to take me to the house where he was born. We walked to an empty neighborhood, there was nothing where his house stood.

G So is memory home? Or in searching for what’s lost, has cinema become home?

KA Cinema more and more. I realize that I can inhabit these places only in the movies I am making.

G At the end of Recollection, a certain freedom is projected, images of people. Can you speak about that scene?

KA I love that scene because it is so hopeful. These phantoms are walking together, hand in hand. They are singing. It is a song where they are declaring themselves. They decide to walk and sing and talk to the world. It’s a final march where these ghosts are no longer ghosts.