Contested Spaces

Kamal Aljafari’s Transnational Palestinian Films1

Peter Limbrick

A Companion to German Cinema, Terry Ginsberg, Andrea Mensch; Wiley-Blackwell Books

2012

A Companion to German Cinema, Terry Ginsberg, Andrea Mensch; Wiley-Blackwell Books

2012

In an online interview to accompany a festival screening of his film Port of Memory (2009), Palestinian filmmaker Kamal Aljafari begins by quoting the German philosopher, Theodor Adorno (2005: 87): “Adorno said, ‘for a man who no longer has a homeland, writing becomes a place to live.’” Reconfiguring that reflection, Aljafari then continues, “For a Palestinian, cinema is a homeland” (Aljafari, 2010). The filmmaker’s citation of Adorno in the course of his interview might profitably be read alongside an epigraph that appears near the beginning of Aljafari’s second film, The Roof (2006). After a brief introductory sequence, we encounter a title on a black background, a quotation from an essay on Palestine by Palestinian writer Anton Shammas (2002: 111): “And you know perfectly well that we don’t ever leave home – we simply drag it behind us wherever we go, walls, roof and all.” Placing these two quotations together, we might say that the second – from Shammas – articulates the conditions under which the first – via Adorno – becomes meaningful for the filmmaker-as-author. That is, if home as place is experienced under erasure for Palestinians who must perforce carry its memory and burdens wherever they go (even within historic Palestine) then under such conditions cinema is one of the few sites in which one can articulate that absent or impossible home; as a transnational Palestinian filmmaker, Aljafari himself does so under material conditions that are highly mobile.

This chapter will consider the films that Kamal Aljafari has made from a German production base and will argue that the politics and aesthetics of his documentary- fiction practice are generated from a transnational frame in which neither Germany nor Palestine/Israel are fixed, unproblematic sites from which to locate or explain his work. I begin from the starting point that German cinema itself has become thoroughly transnational in its production, distribution, and reception as well as in its film narratives, as others have argued (Davidson, 1999; Schindler and Koepnick, 2007; Halle, 2008). Some critical accounts of this transnationality stress the advent of a “cinema of border crossings” best exemplified by the films of Turkish-German filmmakers who critically interrogate concepts of German national identity and global migration (Hake, 2008: 216–221; Halle, 2008, 129–168). But Aljafari’s work demands that we also build an account of media practices whose locations and narrative focus are situated beyond the borders or spaces of Germany and Europe. In The New European Cinema: Redrawing the Map (2006), Rosalind Galt develops a nuanced study of the relationship between aesthetics and politics in recent European films. Galt ends by devoting attention not just to European films that move outside Europe, but even to films like Tsai Ming-Liang’s The Hole (1998) that inhabit a space of transnational production (Taiwanese/French, commissioned within a global art film series of auteur films) while creating an aesthetic at once locally specific and charged with transnational references (in the case of Tsai’s film, through its musical scenes and travel narrative, in particular). Galt concludes that “both industrially and aesthetically, [The Hole] makes us question the ways that disparate places engage with their national, regional, and global histories” (Galt, 2006: 236). Just as Tsai’s careful and aesthetically “spectacular” film resonates with the politics and history of Taiwan even as it is formed out of a transnational film culture, so too are Aljafari’s films embedded within Palestinian history and politics while simultaneously existing within a transnational field of cinematic production in which Germany has provided, thus far, a physical and financial base for his work. Like Tsai (a filmmaker whom Aljafari particularly reveres), Aljafari’s two latter films are completely embedded in Palestinian locations and politics while remaining transnational in their finance, their personnel, and even in their aesthetic which, I will show, deploys the kind of aesthetic beauty and “spectacle” that Galt identifies in some European transnational cinemas. Yet, as I will demonstrate throughout this chapter, whatever his films’ indebtedness to a European cinematic frame, his work studiously refuses Eurocentrism in that it avoids an orientalizing gaze from the position of a Europe looking out to “its others.” Like the work of Elia Suleiman (another Palestinian filmmaker raised in Israel and based in Europe), Aljafari’s films utilize their European art cinema affiliations to expose and subvert Western discourses on Arabs and Arab locations especially as those collude with Zionist narratives of Israel as a model of a liberal democracy.

In many respects, then, Aljafari is typical of the “interstitial” filmmakers discussed by Hamid Naficy in his influential account An Accented Cinema (2001). Rather than assume easy definitions of national agency or, in contrast, complete alterity to the concept of nation, Naficy exposes the way in which many migrant or exilic filmmakers (whose status is definitional of the term “accented” film- maker) inhabit an interstitial mode of belonging with respect to the state: “It would be inaccurate,” he states, “to characterize accented filmmakers as marginal, as scholars are prone to do, for they do not live and work on the peripheries of society or the media or film industries. They are situated inside and work in the interstices of both” (2001: 46). Indeed, Naficy argues elsewhere that interstitial filmmakers “are simultaneously local and global, and they resonate against the prevailing cinematic production practices, at the same time as they benefit from them” (Naficy, 2001: 4). For this reason, Naficy continually stresses complexity and multivocality: funding sources are diverse and often transnationally organized (funding from TV stations, state grants, private money and so on) and production conditions are always “convoluted,” with a mixture of languages, labor roles and conditions, etc. Tellingly, Palestinian-Belgian filmmaker Michel Khleifi is one of Naficy’s case studies for the interstitial mode: a Palestinian born within Israel, Khleifi attended film school in Belgium and retained it as his base. He raised money for his Wedding in Galilee (1987) from a mixture of public and private capital in Belgium, France, Britain, and Germany including TV companies Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen or ZDF (Germany) and Canal Plus (France) (Naficy, 2001: 58–60; Al-Qattan, 2006: 113). Typical, then, of an interstitial mode of production, filmmakers like Khleifi and Aljafari negotiate multiple politics of location and belonging to make films that inevitably stand in ambivalent relation to questions of national produc- tion and nationhood, be it Israeli, Palestinian, Belgian, or French.

As Naficy argues elsewhere (2001: 60–62), the position of interstitial filmmakers is not confined to the cracks within state and private capital: filmmakers like Aljafari are also produced within the worlds of festival programming, academic research and publishing, and university teaching, all of which can establish the artisanal filmmaker-subject as a kind of global commodity while simultaneously offering visibility and agency.2 Since the publication of Naficy’s study, the sources of potential finance for interstitial filmmakers have expanded. In this regard, the production circumstances of Aljafari’s most recent work, Port of Memory, are indicative of the shift occurring in many aspects of Arab arts and culture as the financial center of gravity for artists based in the Middle East and in diaspora shifts from Europe to the Gulf states of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Such shifts, while acting to diversify sources of funding for such transnational productions, nonetheless maintain fundamental aspects of the interstitial and highly mobile modes of practice for transnational Palestinian artists, many of whom cannot freely travel in and out of Israel and the West Bank nor the adjacent Arab states.

From Jerusalem to Köln to Visit Iraq

Aljafari grew up in the town of Ramle, Israel (originally Al-Ramla before Israel’s establishment in 1948) and lived there and in Jaffa through his school years. Attending university in Jerusalem, Aljafari began to immerse himself in cinema by frequenting the Jerusalem Cinematheque. It was at this time that he also began to apply for postgraduate education outside of Israel, influenced, he recounts, by a desire both to study cinema and to “free myself from the status I had as a Palestinian in Israel” by moving outside the country (Aljafari, 2009). Prompted in part by a friend’s move to Germany, Aljafari applied and was accepted to the Kunsthochschule für Medien (Academy of Media Arts, or KHM) in Köln, where he was awarded a Heinrich Böll Stiftung student scholarship in 2000 and went on to complete a three-year MFA degree, concentrating in cinema. There he produced a final-year thesis project, Visit Iraq (2003), and retained Köln as his base to make The Roof (2006) and Port of Memory (2009), as well as an installation project called Album (2008), created for the “Home Works” arts forum in Beirut.

Visit Iraq is a film about an empty space – the abandoned office of Iraqi Airways in Geneva, Switzerland. Aljafari first visited the city shortly after the first Gulf War, where he photographed the street-front office vacated by the airline, which had been subject to a Western embargo at that time. Returning to the site during his time at the KHM, Aljafari decided to organize a film around its exploration and was encouraged by one of his KHM advisors. This particular work, then, emerged directly from his position within the German art academy and was further facilitated by that specific educational environment: Aljafari’s advisor, for example, introduced him to the work of British filmmaker Patrick Keiller, whose film London (1994) made a strong impression on Aljafari for its highly aestheticized exploration of urban space through static, carefully composed shots of the eponymous city, accompanied by an ironic voiceover by an unnamed narrator who recalls encounters with a mysterious character named Robinson. Keiller’s essay film asks complex questions about the political and social aspects of urban space in London but does so in a highly self-conscious style, creating a fictional frame around its documentation of the city by fragment. To make Visit Iraq, Aljafari shot for approximately two weeks in Geneva, constructing multiple perspectives on the empty Iraqi Airways office from a variety of angles: from across the street, with the camera’s object of study refracted through the windows of other shops; at unusual angles from the sidewalk, distorting our perspective of the exterior; from a position pressed against the windows of the office, focusing on the broken furniture and discarded appliances littering the floor (F igure 1).3

Interwoven with the beauty of Visit Iraq’s shots of space is a series of interviews with passers-by who discuss what they know or imagine about the office. Here Aljafari introduces a dry humor into the film in a method quite similar to Keiller’s: the interviews create a composite narrative of the space that veers from the plausible to the outlandish. Aljafari’s “characters” tell stories of bomb scares, mysterious staff movements, and even an elaborate tale of political espionage involving the CIA, Swiss secret service, and Yasir Arafat, that may or may not have anything to do with the empty office. The film’s final credit sequence is bookended by two shots of one of the interviewees who offers an acapella impersonation of a cavalry drum and brass band and then, after the credits finish, creates his own, one-man sound rendition of a cavalry-vs.-Indian charge. While the film proffers nothing definitive about the space it investigates, the viewer is left with a subtle and uneasy sense that this Arab-identified space has been the subject of a kind of everyday surveillance from the city’s European inhabitants, most of whom now have little more than conjecture to offer about its history.

![F1 Exploring an empty space, in Visit Iraq (dir. Kamal Aljafari, prod. Kunsthochschule für Medien).]()

While Visit Iraq was specifically enabled by the KHM and took place under its institutional umbrella, Aljafari by his own account felt remarkably independent during its making, considering himself to have been unconstrained by any kind of institutional, funding-oriented, or nationally-inflected limitations (Aljafari, 2009). His next project, The Roof, however, was the first in which he was required to arrange funding outside of the art school environment. While this process marked his entry into the world of independent production beyond the sponsorship of the academy, it also constituted a rude awakening for Aljafari, who had imagined himself to have secured creative independence along with financial backing. Instead, it soon became clear that the film’s major funder “owned” Aljafari’s artistic choices in ways he had not envisaged. The film was partially financed by Filmstiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen (a state film fund) and the Kunststiftung NRW (an arts organization also from Nordrhein-Westfalen), but the bulk of the film’s finance came from the state-owned German television channel ZDF, still one of the largest funders of German independent film. Aljafari’s proposed film was to screen in ZDF’s “new directors” slot, one which had facilitated many first features, both German and non-German ( Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger than Paradise (1984), for example).

Shooting for The Roof proceeded without incident but, during the editing process, a conflict arose between Aljafari and the film’s German producers. Speaking with hindsight, Aljafari has admitted he was naive to have imagined that ZDF would not wish for a strong degree of creative control; however, a the time, his disavowal of the company’s role led to a dramatic sequence of events in which, after objecting to what ZDF was requiring, he “stole” his footage back from the network’s editing suite, finished his own cut of the film, and screened it at FIDMarseille in 2006 (winning an award for sound design), all unbeknownst to the film’s producers. Seeing the film advertised there, the ZDF belatedly realized Aljafari had completed his film without their assent and sued him. The circum- stances that led to this rupture are undoubtedly symptomatic of the contradiction Naficy (2001: 93) identifies between the artisanal nature of many “accented” films and the simultaneous reality of their dependence on capital. However, the problem of the disagreement, when placed in the context of a discussion of the film’s style, reveals more than simply the creative constraints experienced by artisanal, European-based, interstitial filmmakers. It speaks profoundly to the politics that underpin Aljafari’s careful, precise film – those of being Palestinian within Israel – and the way in which such politics may be rendered or made visible within Europe. I will return to the controversy of production after considering more closely the question of the film’s style and discourse.

The Roof and the Politics of Home

The Roof is a film that can certainly be considered a documentary, although, taking Bill Nichols’ (2001: 99–138) well-worn taxonomy as a guide, one could question the film’s adherence to more common documentary aesthetics by noting its refusal of the expository mode (except for a brief minute of voiceover explanation near the beginning), its reliance only partially on observation (it also places the filmmaker interactively in the frame, in dialogue with its subjects), and its inclusion of elaborately scripted and quite discursively performative moments that utilize nonnaturalistic sound and camera placements. More specifically, I would argue, its form is essayistic in ways that Michael Renov (2004: 109) has outlined: it relies upon a multifaceted approach to past events that “regards history and subjectivity as mutually defining categories” and that constructs a self that is articulated within a broad and complex social sphere. Such an essayistic approach is also, as one might expect, argumentative, although not in a way that lends itself to obvious polemic. By the end of The Roof, one has gained an impression of the marginalized nature of this particular family and its near-mute filmmaker subject as he appears at various moments in the film, but such an understanding is not born of arguments articulated by the documentary characters themselves, nor does the film lay out an extensive historical explanation of the events that have led to this situation. At certain moments, the film does offer scenes in which characters speak of the everyday realities of Palestinian life in Israel. In one such scene, Aljafari’s sister describes to him her job working for an Israeli judge in Jerusalem and the response she gets when speaking Arabic on the street: uncomprehending stares, “as if they do not know that there are Arabs who live here.” In a later scene, a wiry young man speaks directly to the camera (his interviewer is offscreen and unheard) and complains that, with an influx of Russian Jewish immigrants pushing the Arab population from Ramle, Palestinians have become “the tail” of the country. Beyond these brief scenes, however, the film essays its arguments as much through a rhetoric of visual style as through verbal argumentation or spoken narration.

Within this essayistic mode, which eschews exposition for a more complex imbrication of the subjective and historical, the film develops a sustained, almost fetishistic attention to inanimate material objects – the texture of a flat concrete wall, the ruins of a former neighborhood – and to the presentation of found sounds, ranging from the roar of the Jaffa coastline to the chirping of caged birds and the mechanical sounds that accompany work on the ever-enlarging separation wall between Israel and the occupied West Bank (which annexes large swathes of the latter). The Roof constructs Aljafari’s family members as mostly mute characters. In successive scenes we observe his parents, siblings, and extended family in Jaffa engaged in a variety of mundane activities – eating, sleeping, working. But the central conceit of the film, the thing that gives it its title and helps organize its cinematic style beyond the usual genres of documentary, is the unfinished second storey over Aljafari’s family home. Through its obsessive interest in this space, the film develops a style that, while not incompatible with the aims of a social history of Palestinians in Israel, relies more on a spatial discourse that deemphasizes active human subjects and does not rely upon their testimony or visible actions for its impact. Where it engages Palestinians – Aljafari himself, his family, and others they encounter – it places them as bodies within a spatial environment that is structured by a logic of “erasure and reinscription,”4 an environment which they do not appear to actively control. Such processes of erasure and overwriting, common to settler colonial environments more generally, are particularly resonant in the case of Israel/Palestine because of the relatively short and accelerated history of spatial transformation since the end of British Mandate Palestine.5 In constructing a spatial history of Ramle and its surrounding areas and placing a set of subjects (his family) within that history, Aljafari’s film unsettles a dominant mode of media representation in which the state of Israel is depicted as homogeneously Jewish and Palestinians are visible only in relation to the Occupied Territories of Gaza and the West Bank – engaged in conflicts and violent encounters with soldiers and Jewish settlers – rather than also as second-class citizens of Israel itself. Aljafari’s refusal of this kind of dichotomous logic created a crisis for his German funders, whose liberal intentions regarding the prospect of a Palestinian documentary were nonetheless mired in such a discourse of conflict. Moreover, the film questions the “settled state” of Israeli spatial control, insofar as the Jewish state renders invisible and invalid Palestinian claims to a prior and ongoing spatial practice within the terrain now claimed by/as Israel proper. In drawing attention to the colonial politics that have affected all of Palestine, including that part of it which is now Israel, the film essays a deeply complex set of historical events and relationships in the present by showing the sedimented histories of the past as they are found in architectural structures and in uses of space. The family house in Ramle with its half-built roof, never quite “centered” in the frame of Aljafari’s film, stands askew and unfinished as a metaphor for the broken histories and “roofless” state of Israel, with its dispossessed Palestinian inhabitants and its genuinely unsettled Jewish majority.

The house in which we find Aljafari’s family was never really theirs to begin with, we learn. A few minutes into the film, as we move to a static, foreshortened, straight-on shot of the Jaffa waterfront, with abandoned fishing boats, a sea wall, and crashing waves, we hear the following words in voiceover narration, spoken in Arabic and subtitled in English as follows:

While the voiceover proceeds, the camera begins tracking slowly across an empty space of gravel and broken rubble in an abandoned part of Ramle, coming to rest in a static long-shot of the tower of Al-Masjid al-Abyad (Ramle’s “White Mosque”) which appears behind the ruins of a cemetery. We cut from there to two static shots of semideserted Ramle streets, before cutting again to a slow and carefully controlled tracking shot along a concrete wall, a shot held close enough that we can study in detail the texture of the wall which is yet without context as to its placement or function. Cutting from there to a daylight interior shot, the film presents three single beds with three figures napping, and a succession of close-ups: toiletries, family photos, a barred window, a caged bird.6 A man watches television in another room; his daughter prepares food; the young man, who we by now assume is the filmmaker, watches television too; all are silent. The somewhat discontinuous montage of shots continues as we see the family, now numbering six, seated around a table, eating, but barely talking.

The overwhelming impression in this sequence of exterior and interior shots is of staging and of carefully calculated performance rather than straightforward observation: Aljafari’s family seems to be performing a perhaps exaggerated version of itself or, equally plausibly, a script of the filmmaker. The carefully structured views of the exterior streetscape and the slow tracking along the wall, accompanied by nondiegetic music, suggest not the seemingly objective look of an observational film, but that of a carefully framed composition invested in conveying a precise aesthetic impression from the material of the everyday. As we shall see, Aljafari’s most recent film, Port of Memory, takes the already blurred lines between documentary and staged fiction that one sees in certain sequences of The Roof and extends them into the more ambiguous terrain of history and memory. Further, by returning to some of the recognizable subjects of the earlier film (his uncle, aunt, and grandmother) but treating them even more insistently as characters within an ever-more vulnerable and colonized space ( Jaffa), Port of Memory prompts one to interpret The Roof as a narrative primarily about home and its built, lived, buried, and broken properties.

In addressing a spatial politics of home, Aljafari and director of photography Diego Martínez Vignatti, shooting on digital video, offer many shots of flat surfaces and the layers that comprise them, excavating the built environment around Ramle and Jaffa as if an archaeological site. Their camera does so with precisely orchestrated tracking shots or with long static takes that resemble tableaux vivants – one can see movement in the frame, but that movement is minimal and barely disturbs the surface of what seems like a photographic still image. Several examples of this are found in the film’s first few minutes, as the film sets up its montage of Ramle scenes, exterior and interior to the family home. But the focus on built environments and the ways in which they are configured by various colonial practices of appropriation, demolition, or control is a continual issue through the film, resulting in several important scenes. Several of these involve sequences that function like “tours”: in one, we are led by Aljafari’s uncle, Salim, from his house through his neighborhood. As he walks, followed by a handheld camera, we come upon a house whose entire front wall has been reduced to rubble, leaving its interior bizarrely unscathed and open to the elements (Figure 2).

![F2 Urban “renovation,” in The Roof (dir. and prod. Kamal Aljafari).]()

In successive shots through the crumbled masonry and up into its rooms, the building appears like a half-destroyed doll’s house, with beds and furniture an wall hangings still in place amid the ruins in front. One of the owners speaks directly to the camera and to those assembled about how the house had been one of the most ornate and beautiful in Jaffa, and that she will insist it be rebuilt exactly as it was (the “room” in which she stands will appear in a key scene in Port of Memory). Some of the men present, with whom Salim converses, suggest that an Israeli bulldozer “made a mistake” and hit the foundations of the house, triggering a collapse of the wall. Yet the film here suggests that the official explanation of a “mistake” appears unlikely and even disingenuous; Salim’s interlocutors talk about the deliberate “renovation” of the neighborhood by Israeli developers and how that will result in a future neighborhood exclusively for Israeli Jews despite the ongoing presence of Palestinians there even after 1948. This sequence is followed by a silent panning of the camera across the environment immediately adjoining the half-destroyed house, showing us piles of dirt, open lots scraped clean of the buildings that once stood there, and signs of new construction all around. The shot ends on the same stretch of seashore that we have seen previously, with its abandoned, rusted fishing boats, as the sound of waves comes up in the mix and we cut to Aljafari’s grandmother describing again the events of their attempted flight in 1948, including the loss of family members to unrest in Lebanon or bombs in Jaffa as the city fell to the new Israeli forces.7

In this carefully controlled transition from the exteriority of the neighbor’s house to the interiority of the uncle and grandmother’s Jaffa home, the film constructs an historical and political narrative that insists on linking the events of the 1948 War with the dispossession of Palestinian families in Jaffa and Ramle today.8 Rather than through images of overt conflict, The Roof makes its argument about the loss of home through a focus on the often mundane physical properties of spatial transformation and its causes and effects. In this way the film shares much in common with the many recent interventions into Israeli and Palestinian history that focus on architecture, geography, and mapping. Among these many interventions, many of them scholarly or popular written works, are other films too: as Ella Shohat (2010: 278) has reiterated with respect to films about Palestine/ Israel, film work can be “fundamentally historiographical” and one should read such “photographic and cinematic documents as a vital part of the archive and the reassessment of history.” As well as Aljafari’s work, one could point to films like Amos Gitai’s House (1980), which exposes the multiple histories of a house in Jerusalem whose original Palestinian owner lost it to Israel in 1948, after which time it was acquired by the government and rented first to Jewish Algerian immigrants before being sold to an Israeli professor; or the more recent In Working Progress (2006), which follows Palestinian construction workers as they build Israeli settlement colonies in the occupied West Bank.

Writers and scholars have attempted to make sense of what these visual artists have shown so succinctly, focusing attention on the ways that architecture and the demarcation of space are organized within Zionist colonial logics.9 Similarly, in Sacred Landscapes, Meron Benvenisti details the process of literal remapping that Zionist organizations instigated during the British Mandate, the pace of which accelerated as part of official policy post-1948 (Benvenisti, 2000: 12–14). As Benvenvisti shows, the process of remapping had two related aspects: it found Hebrew equivalents or replacements for Arabic names, resulting in a “Hebraization of the landscape” (Benvenisti, 2000: 37), and it reflected the new “facts on the ground” in the wake of 1948: entire Palestinian villages had been razed and no longer existed. Thus the existing maps of Mandatory Palestine, already the result of British imperial practices, enabled a further transformation of terrain such that an extensive Hebrew symbolic system could be constituted over the remains of an Arabic symbolic landscape.10 As Benvenisti explains, this was not limited to the renaming of certain villages, rivers, or sites with biblical Hebrew names – a process that the mapmakers saw as a “national duty” of “redemption” (Benvenisti, 2000: 30–31) – but also extended to creating Hebrew names even where there were no historical precedents for them, transforming Arabic names into similar-sounding Hebrew words or immortalizing modern immigrant Jewish figures with Hebrew placenames (even when those figures had non-Hebrew names themselves) (Benvenisti, 2000: 35–36). The Roof succinctly demonstrates the results of this process in an early sequence around the family home, when a succession of closeups reveals the names of surrounding streets: the English names on the signs are Dr. Koch Street, Dr. Salk Street, Dr. Sigmund Freud Street, but these are inscribed first in their Hebrew versions. While Arabic appears too, the Arabic name is simply a transliteration of the English and Hebrew.

The film continues its focus on the reinscription of space and the elision of Palestinian spaces of home in a sequence set in the viewing tower of a Tel Aviv skyscraper. The filmmaker appears in frame and walks across the empty floor toward a circular wall of windows that offers a full panorama of the Jaffa-Tel Aviv area. As he gets closer, the sound of his shoes squeaking on the polished floor gives way to a close-up of Aljafari wearing headphones, and we hear the sound of the audio tour to which he is listening. A polished American-accented voice begins: “We’re now facing the center of the city that some refer to as the cultural center of Israel – Tel Aviv.” Classical music begins and continues through the voice-off; after a description of the immediate vicinity, the audio tour turns toward Jaffa:

The linguistic slippage around the issue of Palestinian habitation is significant: quickly establishing the Hebrew credentials of the city, the narration makes scant reference to any Palestinian habitation of the town (allowing only for “Arabs” and “Philistines” and relegating their residency to pre-Crusader periods). As Mark LeVine (2005: 28) argues, such a narrative typifies official Israeli tendencies to stress the period of Jaffa’s history from biblical times to the Crusaders while “ignoring the Ottoman period because of the assumption that Palestine experi- enced stagnation and even decline during this time.” Thus, Jaffa was “rebuilt again by the Turks,” according to this narration, but the ellipses between the mentions of “Napoleon’s army” (which invaded in 1799), “the Turks” (Ottomans, who occupied it earlier, in 1517, and then again from 1807), the “British conquest” (1917), and “the Israelis” (1948) render invisible and nonexistent the local Palestinian population, who in fact experienced all of these moments – French and Ottoman rule, British colonialism, and Israeli conquest.11

Aljafari places this eliding narration next to a scene that further exposes and undermines the marginalized position of Palestinians within Israeli discourses of subjectivity and home. Again, the scene relies on a certain performativity and calculated irony rather than on straightforward documentary denotation. A carefully arranged shot shows a cup of coffee or tea next to which an outstretched hand enters the frame to first show and then set down on the table an array of sugar sachets emblazoned with the faces of twentieth-century Zionist leaders. Over this shot we hear the song, “I Believe,” sung in English by the El Avram Group (1995), and in the next shot its refrain, “I exist, I exist, tell the world that I am well/I believe, I believe, I’m the son of Israel,” begins as we see Aljafari slumped in a chair, motionless, in a hotel lobby. The dissonance between the upbeat song and the maudlin look of the film’s authorial subject continues to emphasize the air of passivity and lack of agency that seems to have attached to him throughout. In a drole learning-to-drive sequence, the filmmaker-character is first interrogated by his Israeli instructor’s long list of health and law enforcement questions and then, after first stalling and then making halting progress through the gear changes, is directed into the unpaved streets that lead to the Arab neighborhood of Ramle, where he is warned that the car may be damaged by potholes and unsigned railway crossings. Through the entire sequence, he remains silent, as he does in many earlier scenes within the family home or at his father’s tire shop. In his silence and apparent inability to transcend physically the limita- tions of his environment, his character is thoroughly reminiscent of the character of “E.S.” in Elia Suleiman’s three features, Chronicle of a Disappearance (1996), Divine Intervention (2002), and The Time that Remains (2009), where Suleiman plays a Keatonesque character who resembles the director but is not reducible to him. Aljafari never creates for himself a character by name, but, with the exception of the already-mentioned brief voiceover, the film more often than not positions him as an icon within a diegesis rather than as an authorial subject commenting on the film or explaining things for a viewer.

In two significant sequences in The Roof in which we do see the filmmaker speak, what is said reinforces the literal and metaphorical sense of incarceration and imprisonment that the film establishes. In the film’s opening sequence, for example, Aljafari recounts to his sister the condition of his imprisonment during the first Intifada (for a reason that the film does not disclose), and the description of prison conditions includes a reference to a friend, Nabieh, whom Aljafari later telephones. In that scene, shot at night as Aljafari speaks to Nabieh, who is in Lebanon, via mobile phone, a dominant chord in the conversation is Aljafari’s inability to meet him: as a citizen of Israel with an Israeli passport, Aljafari will not be admitted to most Arab countries. Here, then, the film builds a chain of images that are suggestive of incarceration, as the successive shots of blank walls and surfaces are juxtaposed with personal narratives of a literal imprisonment that also suggest a larger shared sense of entrapment, one in which Palestinian citizens of Israel feel imprisoned by a state that stands in as the locus of “home.”

Moreover, the discussion of the weather and the sound of the sea in Beirut creates a strong sense of spatial proximity despite the supposedly impermeable borders to which the men refer. Aljafari and Nabieh discuss whether or not it’s raining in their respective locations, and when Aljafari asks Nabieh to hold the phone out so that he, Aljafari, can hear the Beirut waves, the soundtrack brings up in the mix the diegetic sound of waves on the beach in Jaffa, which becomes a sound bridge as the film cuts back to that location and a new scene. What figures first as a neat and humorous transition – the wave sounds are louder and carry more fidelity than one would expect from a telephonic transmission – has in effect produced a more meaningful connection, not only bridging the seemingly impossible distance between the two men, who are in fact just a few hundred kilometers apart, but also evincing the historical maritime axis by which the port towns of Jaffa and Beirut were connected in earlier periods. This very axis is what Aljafari’s family tried to access in 1948; its inaccessibility in that time is redoubled in the telephone call, as Aljafari and Nabieh expose the various impediments to travel between Ramle and Beirut, Israel and Lebanon, at this actual historical moment. The waves that connect Beirut to Jaffa, the rain that is falling in Beirut but not yet on Ramle, evoke a Levantine space whose recent political borders, the products of many European colonialisms – British, French, Israeli – belie a far longer history of proximity and interaction between the numerous peoples of the region.12 Thus the film evokes a longer historical sense of home in Palestine, one that is not, as official Zionist narratives would have it, exclusively Jewish or biblical.13 The Roof exposes the pressures on and disavowals of this more inclusive home by an exceptionalist Israeli state whose attempts to write history in an exclusivist and questionable discourse of Jewish ethnonationhood are rendered quietly obvious and absurd by the film.

I have suggested, then, that Aljafari’s film, with its interest in home and built spaces, deploys a carefully stylized cinematic discourse to render visible the logics of Israeli urban planning, historiography, and spatial conquest and their dehumanizing effect on Palestinians in “the interior.” That is, The Roof demonstrates that the “1948 Palestinians” are effectively invisible to the state except to the extent to which they occupy a marginalized position within Zionist discourse, one in which they are made to signify a pathological premodernity and backwardness before the coming-into-being of the modern Israeli state. Shohat (2010: 106) reminds us that Golda Meir also famously constructed Mizrahim, or Oriental Jews, in such a fashion, considering them to have arrived unevolved from another time: “Shall we be able to elevate these immigrants to a suitable level of civilization?” she asked. As Shohat shows, the “Arabness” both of Mizrahi Jews and Palestinian Arabs is constructed within a racialized discourse, while the differential position of Israel’s various populations results in a complexity that is belied by simplistic constructions of “Arab vs. Jew” or “Arab vs. Israeli” (Port of Memory will embody this recognition even more overtly). Thus The Roof seems to offer in its slow-moving images and near-mute characters a fragmented nonidentity as a direct result of a colonial state logic, and the film – in its concentration on rubble, walled surfaces, incompletely buildings, and spatial divisions – cinematically constructs a fractured and ruinous home space whose many-layered past is contrasted with the eerily smooth surface of the separation wall which dominates the film’s final scenes. I have written elsewhere that this cinematic style creates an effect that is uncanny and even queer in its discursive effects: the gendered masculine authority of the filmmaker is undermined rather than recovered, and the Palestinian family is rendered such that it appears pathological within heteronormative Zionist ideology (Limbrick, 2011). Rather than contest suchsigns of lack with a compensatory filmic mechanism of explicit nationalism, however, the film uses the marginality of its characters as a means to unsettle and expose the discursive logics of Zionism, revealing its structuring logics of racism and spatial hierarchization.14 Moreover, the film also rejects the familiar documentary iconography of Palestine. Aljafari’s characters (and, as we have seen, they appear to us more as characters than as documentary subjects in privileged relation to the real) do not appear in the positions or settings in which many non-Arab audiences are used to seeing Palestinians appear: in contrast to mass media representations, they are not traversing checkpoints within the West Bank or crossing into Israel, they are not in visible conflict with Israeli soldiers, they are not protesting or waving flags or being shot at; in other words, they do not conform to the limited and partial imaginary created in and for the West as the result of decades of occupation, resistance, and conflict. It was precisely this absence that perturbed the ZDF representatives who shared the editing suite with Aljafari in his first attempts to cut his film.

The production liaison, relates Aljafari (2009), would take copious notes during his viewing of the rushes, scribbling in a notebook as Aljafari’s images appeared on screen. At first the ZDF representative did not impose judgment or demands; eventually, however, he became more vocal. He could not understand why Aljafari’s family members “looked more Italian” than they did Palestinian, why they “talked so softly,” and why nothing seemed to happen in his film. What was required, he argued, was a voiceover to explain things better to an audience, and more conflict between the characters and their setting. Certainly we can attribute such comments in part to the contradictory conditions of production already noted in the artisanal mode of film practice; the avowedly noncommercial filmmaker with his personal vision placed in direct conflict with the capitalist mode of production that he depends upon, in the personage of a producer whose desired choices rest on a presumed threshold of audience comprehension and accessibility. One must at the same time, however, recognize the overdetermined cultural logic of such a scenario: a transnational and interstitial filmmaker, whose work creates a critical engagement with notions of home by essaying the internal displacement of his subjects, is here pulled back into his European production context – one that financially enables his work but that refuses to “see” its critical vision of Palestinian life inside Israel. The German producer’s inability to countenance Aljafari’s images reveals a kind of nativism that cannot see “1948 Palestinians” because it recognizes Palestinians solely as a people geographically external to a bounded and bordered Jewish state with which they are in combat. Such a misrecognition of the realities of Palestinian life across all of Palestine/Israel, not only Gaza and the West Bank, reorientalizes Palestinians and fails to comprehend the specificity of spatial destruction and reinscription that The Roof presents.15 Further, and more disturbingly, the funders’ call for more visible conflict and expression of an oppositional Palestinian-ness evinces a desire wrongly to transform questions that the film demonstrates are political – having to do with colonial policies and spatial control – into a singular and dichotomized issue of ethnic or religious identities in conflict. The desire for a more simplistic and obfuscatory discourse on Palestine/Israel is, of course, neither generalizable across all German settings, nor is it only found in Germany; my point is rather that it represents a logic that is both Eurocentric and ultimately coextensive with ideological conceptions of a homogeneous Jewish nation locked in inevitable and timeless conflict with non-Jewish antagonists. As a logic, it depends upon a constructed binarism between Western/European/ modern settings and non-Western/Arab/primitive ones and is thus antithetical to Aljafari’s films in which the discourse on home is irresolveably produced across axes of difference, through multilayered histories, and across borders. Against the reductive tendencies embraced by his German producers, Aljafari’s cinema is neither programmatic nor driven by simplistic or literal-minded expositions; rather, it is attentive to the small details that render “Palestine” an unrealized or yet-untenable concept within the current incarnation of a settler state.

Port of Memory and the Spatial Politics of Jaffa

In Aljafari’s most recent work, Port of Memory, the politics of home within the “unsettled” settler state are presented even more keenly as producing a kind of slow-burning psychological damage. While the sense of suspended animation created in The Roof’s domestic settings is continued in the latter film, here an even more disquieting air of collective trauma prevails, manifest in disturbing images of Jaffa residents who have seemingly gone mad. Like Aljafari’s two previous films, Port of Memory is evocative of a very particular locality and space – the neighborhood of Ajami in Jaffa – but it is also a film that, beyond the intense localness of its representation, demonstrates even more compellingly the relativity of Aljafari’s German production base and the increasingly decentered and transnational scope of his practice. The film again received funding from Filmstiftung Nordrhein- Westfalen and postproduction was carried out in Munich, but this time financial support for the film came from a diverse list of parties that included the Sundance Institute (from which he received script development funds), the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (based in Jordan), Fonds Sud Cinéma (France), the Ministère des Affaires Etrangères et Européennes (France), Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication CNC (France), and the Middle East International Film Festival (since renamed the Abu Dhabi film festival), whose funds reserved the right to premier the film at their festival. Certainly all European-based filmmakers are now familiar with a degree of transnational funding but, as Randall Halle (2010: 306) explains, many European funds are also now explicitly addressed to filmmakers in and from the Mediterranean and North Africa. Aljafari’s project stands between these different strands of transnational production, since he has worked from a European base and is thus eligible for local sources such as German television, but he also inhabits the role of a Palestinian filmmaker on a transnational stage, which places him within the orbit of funds external to Europe or earmarked for Arab or Middle Eastern filmmakers. These sources of capital extend as far as the United States, and not only via festivals like Sundance: Aljafari completed the subtitling of Port of Memory while a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard University.

Thus, the financing of Port of Memory is indicative of two major cultural and political trends that contextualize the transnational coordinates of his practice over these three films. One is the increased interest in Middle Eastern cultural production on the part of US funds, as evidenced by Sundance’s support. In part as a consequence of the post-9/11 political environment (in which government and nongovernment organizations have been more actively engaged in projects of “cultural bridge-building”), some US arts and cultural organizations are increasingly engaged in sponsoring Arab or Middle Eastern projects, both those that originate from within the United States itself and those that take shape internationally. As examples of this trend one might point to the success of an organization like ArteEast, which, as a nonprofit, has been able to secure US philanthropic funds for the curation of important, well- publicized programs of Arab films and art at venues like Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art and has toured them at universities, schools, and museums. The magazine Bidoun, based in New York but with founding editors and writers based in Dubai, Beirut, and other key transnational Arab cities, has become part of the international cadre of art/culture magazines. At the same time (and often in conjunction with US organizations and institutions), the past decade has seen new projects of massive capital investment in arts and education infrastructure within the Gulf states of Qatar and the UAE. Major new museums have opened or are under construction in Dubai, Doha, and Abu Dhabi; film festivals in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Sharjah have recruited famous international directors and curators and continue to create new funds for filmmakers. In Qatar, the Doha Tribeca Film Festival was launched in 2009 as a joint venture between the Doha Film Institute and the Tribeca Film Institute (based in New York City), and the Doha Film Institute is positioning itself as a financing source for film production as well as promoting an educational program of workshops, creative labs, and short film competitions. Such initiatives, financed jointly by the oil wealth of Emirati and Qatari governments and the cultural and financial capital of US institutions, are not only transforming the coordinates of local production in the region in their attempts to create a culture industry in the Gulf, but are also simultaneously challenging the earlier primacy of established European sources like Fonds Sud or Arte television. Thus we might position Aljafari’s film, like the work now in production by many other Arab filmmakers, within the shifting coordinates of arts funding that is increasingly located in the Gulf states and is articulated to new centers of global finance.16

Port of Memory extends some of the preoccupations that Aljfari has developed as a filmmaker in both Visit Iraq and The Roof. However, it essays even further the dislocated politics of home that the prior films addressed. It does so, first, by loosening a relationship to the real through an even more hybridized form of documentary fiction. As in The Roof, members of Aljafari’s family play key roles. Shot partly in their actual house, the film centers around the home of Aljafari’s uncle, aunt, and grandmother which is threatened with acquisition by the Israeli state. As the film begins, Salim pays a visit to his attorney, who remains offscreen and casually reports that he has lost the deed of title to Salim’s home. Through the course of the film, we return to the same living room and to conversations conducted between Salim and his sister, Fatmeh (Aljafari’s aunt) about the immediacy of the eviction threats to which they, and the Palestinian families around them, are subjected. The film develops this sense of attenuated life by alternating scenes of the domestic rituals of a middle-aged woman and her mother, whose home we have in fact seen in The Roof; it is the house damaged by a bulldozer, now repaired. The film also stresses the extreme psychological toll experienced by Palestinians within this environment by returning to other characters whose actions are disturbing or inexplicable. One such figure (whom we have already seen in the lawyer’s office, too) is placed in a kind of sparsely furnished working-men’s club, where he and two older men pass their time wordlessly, watching television, staring vacantly across the room, and tending a charcoal grill, respectively. In the first scene in which we are introduced to this character, he uses tongs to pick up a glowing coal which he proceeds to hold just centimeters from his neck as it undoubtedly begins to burn his skin. The television in the club displays a broken and repetitive excerpt from the Chuck Norris film, The Delta Force (1986), whose production, as I will show later, violently affected Jaffa’s urban fabric; in effect, the older man watches the televised reoccupation of his neighborhood from within its very ruins. Another character who is central to the film’s mood, yet who remains unnamed and without dialog, is a young man on a scooter who, upon his first appearance in the film, rips his helmet from his head, throws it to the ground, and begins screaming uncontrollably without provocation. And, at significant moments in the film, we see a close-up shot of the hands of Aljafari’s aunt, who washes at the sink in a slow and beautifully choreographed ritual that nonetheless has the appearance of an obsessive-compulsive behavior. By the end of the film’s remarkably simple narrative, Salim dreams that his lawyer locates the missing title, but visits his office one more time, only to find it vacant, its occupant disappeared without explanation.

The film thus stages this simply sketched story within a larger, nonnarrative discourse that reflects the actual logic of dispossession currently taking place in the Jaffa area. As does The Roof, Port of Memory exhibits a documentary attention to built environments, especially those under demolition and construction: we see signs of new housing developments for Israelis and a public park at the water’s edge, and examine the scars of neglected or damaged buildings that are being torn down or renovated by Israelis in search of “authentic” and “historical” environs with which to construct a “New-Old Jaffa” next to modern Tel Aviv (LeVine, 2005: 226–248). However, this documentary material becomes a scaffold for a series of vignettes that further test the borders between documentary and fiction and combine to render Jaffa a densely conflicted and multilayered space. Signaling the ongoing way in which everyday relations between residents are constructed within a dynamic of urban renewal and dispossession, Aljafari constructs a scene in which a young Israeli woman comes to the door of Salim and Fatmeh’s home to ask politely but insistently, in Hebrew, if it is for sale or if she can at least enter and look around. This scene, isolated in the film (we never see the visitor again) is nonetheless contextualized by other shots in which we see posters lamenting the loss of Palestinians in the neighborhood (“we miss you,” says their text in Arabic), flyers encouraging residents to call if a home is for sale or rent, and leaflets that document evictions of Palestinian families, all of them signs from the actual lived reality of Jaffa. In a decision that was again the source of some dissent between Aljafari and one of his producers (this time French), the subtitling of this sequence for European and US release prints did not signal the linguistic shifts from Arabic to Hebrew and back. While his producer insisted upon a need for clarity in light of her audience, Aljafari maintained that leaving the languages translated but unmarked was consistent with the spatiopolitical realities that he was documenting, in which language usage, as much as architecture and history, becomes multilayered and inseparable from the issues of proximity, memory, and loss that his film essays.17

Aljafari further dramatizes the continual Israeli expropriation of Palestinia property in a short but evocative sequence that is set in the same living room of the house we saw in The Roof. There, the camera arrives to take measure of a bulldozer’s assault on a Palestinian home whose entire front wall has been ripped off. Its owner vows on film to have it rebuilt, and in Port of Memory, Aljfari returns to that home. Now, the front of the building has been rebuilt, although one can trace the vertical line in the plaster where the repaired wall is grafted onto the original structure. We first see a small group of people moving furniture and taking down paintings from the wall, including one of Jesus’s “last supper.” In a room to the side, a woman and her elderly mother sit on the bed watching. Then, the small film crew sets up a shot in which an Israeli man stands under an ornate door lintel and proclaims proudly, in Hebrew, that he built the decorative stained glass windows above him with his own hands. The director orders multiple takes so that his actor might inflect the statement convincingly, and asks him to add a line about the ceiling, too, urging him to “say it like you really own it.” While the scene is not explained, taken together with other such ambiguous vignettes, it generates the overwhelm- ing sense that a Palestinian architectural history is being erased and rewritten through multiple means, including the cinematic. Later, as we shall see, Port of Memory uses extant Hollywood and Israeli features to further expose the remapping of Palestinian space within fictional diegeses, but here the viewer of The Roof is privileged for having seen this house once “exposed” by dint of its partial destruction by a bulldozer, and now “reexposed” and threatened once again through a fictionalized cinematic encounter (of the kind that has occurred throughout Jaffa’s history and that continues still).

For while this film-within-a-film scene rings uncannily “false” as documentary (we sense its performative staging), it is nevertheless firmly embedded within the actual politics of Jaffa’s Arab neighborhoods. In a final chapter committed to theorizing a space of conviviality between Palestinian and Jewish Israeli residents, LeVine (2005: 215–248) takes up the contemporary politics of the “New-Old Jaffa.” He emphasizes the way that Jaffa exists within Tel Aviv’s dualistic imaginary – as simultaneously a dilapidated, violent, dangerous streetscape ready for transformation and renewal, and an “ancient,” “romantic,” “exotic,” and “historically Jewish space, one that was ‘liberated from Arab hands’” to become available for development “as a cultural and historical center” (2005: 220). Crucially, LeVine points out that such an ideological construction of Jaffa derives in part from moving-image cultures of television and film which are not incidental to the forces of dispossession that have grown around Jaffa, having in fact been complicit with the very destruction of neighborhoods that “urban renewal” later officially codified. LeVine, quoting Andre Mazawi, notes that Jaffa, and especially the neighborhood of Ajami, in which Port of Memory takes place, “is the site of many crime and war movies and television shows since the 1960s because ‘it resembles Beirut after the bombardments – dilapidated streets, fallen houses, dirty and neglected streets, smashed cars’” (2005: 220).18

Among the many unnamed films that LeVine and Mazawi allude to, two in particular are relevant here: Kazablan (1974) and The Delta Force, both directed by the Zionist Israeli director Menachem Golan. Kazablan, a musical, was part of the genre of “bourekas” films, dominant in Israeli cinema between 1967 and 1977 (Shohat, 2010: 113), which projected fantasies of reconciliation between the deeply divided and socially stratified communities of Ashkenazim (Central and Eastern European Jews) and Mizrahim ( Jewish Arabs) within Israel, often through exaggerated stereotyping. Kazablan (sometimes spelled Casablan, after Casablanca), played by Yehoram Gaon, is a Moroccan Jew who falls in love with a young Ashkenazi woman. Her family eventually accepts him, but not before he has spent most of the film socially ostracized by his Ashkenazi neighbors, who refer to him and his Arab friends with racialized insults like vilde khaye (“wild animal”).19 Kazablan’s setting is the same Jaffa neighborhood as in Aljafari’s film, but in Golan’s film it is populated only by Jews, both those of Mizrahi and Ashkenazi origin. The government wants to tear down their dilapidated homes, but the residents band together to restore the buildings for themselves. In a sentimental musical sequence in the film, Kazablan wanders the seafront streets of Jaffa, singing nostalgically in Hebrew of his homeland in Morocco, a place that he remembers as paradise before the displacement and loss that he experiences in Israel. No less important for its role in Jaffa’s cinematic history is Golan’s later film, The Delta Force. Here Chuck Norris appears as a US commando, fighting Palestinian “terrorists” in the midst of civil-war-torn Beirut.20 The production team of The Delta Force not only took over Jaffa in order to cast it as Beirut but created its own urban mayhem in the process. As part of what Aljafari (2008) has termed a “cinematic occupation,” the producers arranged for their fictional conflicts to include actual explosions that destroyed real buildings, thus provoking real consequences for Jaffa’s residents and its ever-more-threatened built environment.21 Elsewhere, Aljafari has spoken about being a child in Jaffa during this period, watching the explosions as the city was transformed around him.

These two films, then, have production narratives that are thoroughly embedded in the layered histories of spatial exploitation and transformation that have built and unbuilt Jaffa. Kazablan depicts – and both films figure in – a politics of social relations and urban practices that writers like Monterescu (2007) and others (Tamari, 2009; LeVine, 2005) have documented and analyzed. Port of Memory forces a reflection on the uncanny (literally, in Freud’s terms, the unheimlich or unhomely) effects of watching and experiencing such filmic narratives from a subject position inside that urban space of home.22 For a Palestinian in Jaffa, we might say, now internally displaced and denied a genuine homeland, this kind of cinema contributes even further to the erasure of that space.

With such erasures in mind, Aljafari’s decision to integrate sequences from both films within the diegesis of his own, unmarked and unannounced except for a reference in the end credits, constitutes a radical gesture that further intervenes in the spatial politics and critiques that others have advanced around the site of Jaffa. In The Roof, as we have seen, Aljafari’s uncle takes a walk around his neighborhood and leads the viewer in a tour of demolition and urban gentrification. In the newer film, Salim sets out on another walk in the same neighborhood, but this time he becomes a kind of ghost, haunting the mise-en-scène of Golan’s film, Kazablan. Aljfari inserts an entire sequence constructed from pieces of Kazablan: as a shot is held of Salim looking out over the ocean, music from the earlier film comes up in the mix, and we cut to a shot of the Jaffa waterfront where children play as the camera pulls back and pans right to reveal Kazablan beginning to walk into frame. He sings in Hebrew, subtitled as: “There is a place beyond the sea where the sand is white and home is warm,” and the camera tracks and follows him as he continues a walk from the oceanfront into the streets of Jaffa, all the while singing nostalgically of the “home beyond the sea,” the neighborhoods he left behind, the women and children playing while the sabbath bread bakes in the oven. In this original sequence, Kazablan continues his walk through the derelict streets of Jaffa, further establishing for the viewer the harsh conditions for Mizrahi Jews who found themselves caught between the Zionist vision of a Jewish homeland and the realities of prejudice in the (usually ghettoized) neighborhoods or camps that they were placed in upon arrival.23 Kazablan’s neighborhood is portrayed as somewhat mixed, but only between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim, in keeping with the film’s endeavor to project a multicultural space of Jewish nationhood, one that excludes Palestinians entirely.

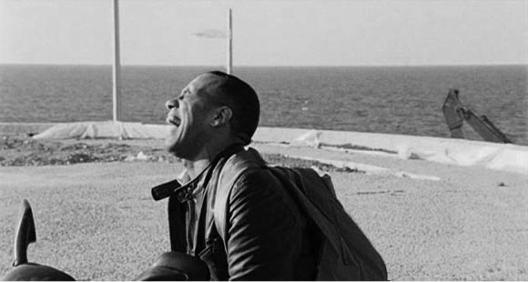

Indeed, in Kazablan, while the neighborhood is subjected to the same threat of evictions and gentrification depicted in Port of Memory, the former removes Palestinians entirely from the diegesis. Consequently, as Kazablan’s promenade proceeds in Aljafari’s film, we begin to see a ghostly reclamation of the original material. As Kazablan rounds a corner and walks down an alley, Salim enters the frame from behind a building, catching a quick glance at the newcomer before retreating behind a wall (Figure 3). In the next shot, Kazablan continues his walk toward the camera as Salim again materializes within the frame and quickly overtakes him as he leads the way through the empty lane. From this shot on, the mise-en-scène of Kazablan continues, but its protagonist is replaced by the figure of Salim, who “ghosts” each shot as he continues the walk around Jaffa’s streets in a scene that also incorporates material from two later sequences in Golan’s film (a walking sequence after Kazablan is released from prison, and a scene in which his lover, Rachel, visits him at his house; there Salim replaces Rachel (Figure 4)). The effect of the collapsing diegeses is extremely disorienting since the bleached-out color of Kazablan’s diegetic world here contrasts slightly with Alajfari’s own footage in the preceding and subsequent shots;24 even a viewer who has not seen Kazablan will likely notice that something is awry in the sequence. Aljafari also removes the sound from the original footage, now constructing a walking sequence with only the sound of Salim’s footsteps reverberating loudly, and the noise of the wind continuing through each subsequent shot.

![F3 Salim reinhabits Jaffa, in Port of Memory (dir. Kamal Aljafari, prod. Novel Media).]()

![F4 Ghosting Kazablan, in Port of Memory (dir. Kamal Aljafari, prod. Novel Media).]()

The merging of diegetic spaces that Aljafari effects is critical for the film’s intervention into the spatial politics of Jaffa and for the question of cultural memory that is alluded to in the film’s title. The sequence effectively remaps Golan’s Jaffa – ethnically-cinematically cleansed of Palestinians – with the ghostly body of a Palestinian resident present throughout yet absent to the diegetic world of a Zionist cinema like Golan’s. Aljafari renders visible the “repressed Palestine” (Shohat, 2010: 282) that Golan’s film strives to cover over and, in so doing, creates a sequence that relies on a productive haunting of nationalist space by that which it represses. In her book Ghostly Matters, Avery Gordon (2008: 63–64) repositions the ghost as a “social figure” who “imports a charged strangeness into the place or sphere it is haunting.” Producing a sense of the uncanny in those who perceive it, the ghost operates as “a symptom of what is missing” but also “represents a future possibility, a hope” and, finally, demands that we “offer it a hospitable memory out of a concern for justice” (emphasis in original). Aljafari’s ghostly uncle here recaptures the space from which he was excluded, evoking the Palestinians missing from Kazablan as well as those alluded to in the posters, seen earlier, which line the streets of Jaffa, thus demanding justice in the present. Yet the sequence does so through an articulation of cultural memory that, like the space of Jaffa itself, is itself layered with competing languages and allegiances.

The sequence in fact complicates an ethnically oppositional reading of Palestinian–Jewish conflict by relying heavily on the evocative music and lyrics of the Hebrew song that Kazablan sings. This song is one of exile, but its evocative construction of Morocco is here retooled for another’s exilic yearning. On the one hand, the sequence functions to reinhabit and reclaim a disappearing Jaffa on behalf of those displaced in the past and those threatened with displacement in the present (the very next shot is a slow vertical pan across a broken terrain that includes the detritus of buildings already destroyed). But it is also the song of the exilic and transnational filmmaker. Aljafari (2009) has referred to the Kazablan number as his song, too: “feeling displaced and missing home, that’s my narrative!” In representing that narrative for himself, however, Aljafari nevertheless retains the Hebrew song and music from the original film, which are not mixed out until late in the sequence. Part of his intervention, then, is to allow the Hebrew language to serve as the narration for a Palestinian experience, in much the same way as Shammas, cited in the introduction to this chapter, did with his groundbreaking novel Arabesques (1988), written in Hebrew. Aljafari does so in full knowledge of the potentially controversial implications of that choice from the standpoint of Palestinians who regard Hebrew as the language of the occupier; yet, as he (2009) has said, “it’s just a language; you can feel with that language,” and his implicit recognition of the polyglot nature of Palestinians within Israel was confirmed for him at the film’s première in Abu Dhabi where, he recounts, many Arab audience members commented on how emotional they felt at hearing the song and seeing the sequence. In this respect, it is significant, too, that the two women whose house is taken over for the film shoot are Christian. In one scene, we see the younger woman praying before a makeshift domestic shrine of candles and religious icons; in a second, disarmingly funny, sequence, we observe her and her mother watching a televised scene of Christ’s baptism by John the Baptist, as their cat sprawls out on top of the VCR and TV, twitching when a dove appears as the Holy Spirit. Port of Memory, then, depicts Jaffa as a multiconfessional space whose conflicts are generated by historical and contemporary acts of colonization and not by the identifications of religion, ethnicity, or language.

If Aljafari’s use of Kazablan perhaps offers the ghostly promise of a reclamation of fictional history toward recognition of actual Palestinian presence,25 Port of Memory’s incorporation of a clip from The Delta Force, which introduces the film’s final scenes, reminds us that Israel’s cinematic and real occupation of Jaffa continues into the present. As we have seen, Salim’s carefully shot and structured walks in Jaffa in this film and The Roof serve to remap the city as a site of continuous Palestinian habitation and history, recording built spaces that are at risk of destruction as well as those that have been transformed by years of use and reuse as the town is reinscribed with other histories and policies. As the Kazablan walk concludes and we return to its establishing shot of Salim looking out to sea, we cut to a long-shot of a hillside that has been razed and refigured as a kind of memorial park of picnic tables, a lookout, and flagpoles, its slopes punctuated by lonely streetlamps and empty roads. Following this bleak panorama, one that is tellingly reminiscent of the suspended space and “empty” shots at the end of Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Eclipse (1962), we see Salim descending a flight of steps. We have seen the same street earlier in the film but this time, as Salim passes out of frame, there is a cut to a tighter framing of a street scene in which we recognize an almost completely identical architecture. Suddenly, a Volkswagen van careens down the steps with a jeep speeding after it, as if chasing Salim, as the sounds of automatic weapon fire and an offscreen helicopter accompany the screech of engines: The Delta Force has invaded Jaffa. Chuck Norris leans out of the van, firing back at his pursuers, and a gun battle continues in successive shots as the van speeds through the Jaffa streets. Aljafari’s insertion has removed the implied diegetic location of Beirut from the mise-en-scène, placing the American film and its imagined street fight between US soldiers and “Arab terrorists” back into the Jaffa neighborhoods in which the production actually took place. The scene is brief, ending with a shot of a minaret that we have seen in the Kazablan sequence as well as earlier in Port of Memory, but the effect is to further stress the operation of a “force” of colonial image-making upon Jaffa. The full effects of such force are shown to the viewer shortly after, in one of the film’s concluding and most disturbing images. In an extreme long-shot, the unnamed motor-scooter rider returns to the memorial park. As the camera cuts in closer, it isolates him at the top of the hill, sitting on his machine, laughing maniacally as the crab-like arm of a digger appears just over the crest of the hill; his face, the film suggests, is the face of an Israeli-colonized Jaffa (Figure 5).

![F5 The face of colonized Jaffa, in Port of Memory (dir. Kamal Aljafari, prod. Novel Media).]()

Conclusion

In this series of three films, Aljafari establishes himself as a Palestinian artist whose work is produced interstitially and financed transnationally through a wide variety of sources.26 While his work, like that of many German filmmakers, has relied upon a mix of European funds, his own geographical mobility and the emergence of new Gulf film production funds have oriented him toward other sources, too. Aljafari’s focus on predominantly Palestinian locations and narratives and his deployment of an aesthetic honed within a European art and film context situates him within a small stable of other Palestinian filmmakers working on “Palestine-in-Israel” from a position of exile (Shohat, 2010: 276; Alexander, 2005: 154). While one can historically situate Aljafari’s emergence as a filmmaker within such a context, or even within the domain of interstitial accented filmmakers more generally, this chapter has argued that Aljafari’s work is distinctive in its consistent focus on a spatial politics of home in Palestine/Israel, rendered in a style in which long-shots, minimal action, and an obsession with physical surfaces builds a highly political and poetic discourse even, or especially, in the absence of a declarative political rhetoric from the film’s ambiguous characters. In so doing, if Aljafari approaches the goal signified by his own quotation of Adorno – in which cinema becomes a homeland for a people that has none – then it has been by reestablishing a Palestinian presence within the contingencies of colonial space as it is wrought by the Israeli state. His cinematic homeland is one which never carries the force of an easy or utopian nationalism and yet, in exploring the layers of the past, his films still offer the material for a possible future out of the rubble of the present. If one might risk a hopeful note in closing, it could be this: While the production history of Aljafari’s The Roof shows the need for the filmmaker’s vigilant resistance to the Eurocentric vision of Palestinians that his German producers wished to present, the recent success of Port of Memory in European festivals27 might be one sign that his work is finding an audience that wants to see Palestine differently.

This chapter will consider the films that Kamal Aljafari has made from a German production base and will argue that the politics and aesthetics of his documentary- fiction practice are generated from a transnational frame in which neither Germany nor Palestine/Israel are fixed, unproblematic sites from which to locate or explain his work. I begin from the starting point that German cinema itself has become thoroughly transnational in its production, distribution, and reception as well as in its film narratives, as others have argued (Davidson, 1999; Schindler and Koepnick, 2007; Halle, 2008). Some critical accounts of this transnationality stress the advent of a “cinema of border crossings” best exemplified by the films of Turkish-German filmmakers who critically interrogate concepts of German national identity and global migration (Hake, 2008: 216–221; Halle, 2008, 129–168). But Aljafari’s work demands that we also build an account of media practices whose locations and narrative focus are situated beyond the borders or spaces of Germany and Europe. In The New European Cinema: Redrawing the Map (2006), Rosalind Galt develops a nuanced study of the relationship between aesthetics and politics in recent European films. Galt ends by devoting attention not just to European films that move outside Europe, but even to films like Tsai Ming-Liang’s The Hole (1998) that inhabit a space of transnational production (Taiwanese/French, commissioned within a global art film series of auteur films) while creating an aesthetic at once locally specific and charged with transnational references (in the case of Tsai’s film, through its musical scenes and travel narrative, in particular). Galt concludes that “both industrially and aesthetically, [The Hole] makes us question the ways that disparate places engage with their national, regional, and global histories” (Galt, 2006: 236). Just as Tsai’s careful and aesthetically “spectacular” film resonates with the politics and history of Taiwan even as it is formed out of a transnational film culture, so too are Aljafari’s films embedded within Palestinian history and politics while simultaneously existing within a transnational field of cinematic production in which Germany has provided, thus far, a physical and financial base for his work. Like Tsai (a filmmaker whom Aljafari particularly reveres), Aljafari’s two latter films are completely embedded in Palestinian locations and politics while remaining transnational in their finance, their personnel, and even in their aesthetic which, I will show, deploys the kind of aesthetic beauty and “spectacle” that Galt identifies in some European transnational cinemas. Yet, as I will demonstrate throughout this chapter, whatever his films’ indebtedness to a European cinematic frame, his work studiously refuses Eurocentrism in that it avoids an orientalizing gaze from the position of a Europe looking out to “its others.” Like the work of Elia Suleiman (another Palestinian filmmaker raised in Israel and based in Europe), Aljafari’s films utilize their European art cinema affiliations to expose and subvert Western discourses on Arabs and Arab locations especially as those collude with Zionist narratives of Israel as a model of a liberal democracy.