25 Encounters:

Rutger Wolfson & Kamal Aljafari

Ruger Wolfson

& Kamal Aljafari

25 Encounters

IFFR – International Film Festival Rotterdam

May 04th 2022

25 Encounters

IFFR – International Film Festival Rotterdam

May 04th 2022

Former IFFR director Rutger Wolfson (2007–2015) meets with Palestinian filmmaker Kamal Aljafari, to discuss the poetic potential of found footage cinema, and reflect on the powerful connection between film and the art space.

Moderated by IFFR programmer Janneke Langelaan.

![F1 Still from An Unusual Summer, Kamal Aljafari, 2020]()

RW We’ve never met before, right?

KA No, but your face is familiar. I think I’ve seen you around the film festivals, probably many years ago in Rotterdam as well. Rotterdam was my first festival ever, back in 2003. I was still living in Cologne at that time, so it was very close.

RW Were you here with a film or were you just visiting?

KA I came with a bunch of students to watch movies. Rotterdam was the place to be, back then. All these Asian films were coming into the festival, so we had to come and watch them.

RW Just curious – where are you right now?

KA I’m in Berlin. I’ve been living here since 2011.

RW I lived there as a student for about half a year. It was right after Die Wende, when the Wall came down. It was an amazing time, a collision of two worlds, like history happening right in front of your eyes.

KA Yeah, that’s a bygone era.

RW It’s just a big city now.

KA It’s a normal place again.

RW But still a nice place to live. I’m calling you from my home in Rotterdam. I started out working in the art world as a curator and a writer of essays about art theory. Somehow, by miracle almost, I became the director of IFFR. They couldn’t find anybody else to do it, I guess. During my time as a curator, I think I organised around one hundred exhibitions. I was quite tired of constantly coming up with new ideas and spending that energy you need to give to these exhibitions, so I was ready for something new. Now I’m working for a debate institute [Arminius, ed.]. I don’t know if you’re familiar with this kind of format, but in the Netherlands and some other places in Europe, you have these places where public debate is organised. Public debate is considered to be highly important to democracy here, so there’s some funding to make them take place, which is a nice thing to do. Now, I’m also in the middle of a super scary and fun creative project, which I’m very excited about: I’m making a short film. I finally get to be in a slightly more creative position. You know, working at the debate institute is fine and the job at IFFR was super nice, but it’s not very creative work – you’re more part of management, trying to make a place for filmmakers and artists to share their work. I feel happy and kind of privileged that I’m now in a position to make something of my own.

KA That sounds beautiful! I’m in my own place as well. I’m editing this new film and dealing with all this technology. Basically, I’ve worked from home for many years now. The last three films I did, were mostly made with already existing footage that I, in fact, didn’t shoot.

RW I saw two of your films, I saw An Unusual Summer (2020) and…

KA Recollection, maybe?

RW It’s with the numbers in the end…

KA Ah! It’s a Long Way from Amphioxus (2019). It’s a strange movie.

RW No, it’s lovely!

KA I shot it in Berlin, in the so-called Ausländerbehörde, which is the building where people go to apply for asylum, or even just a normal residency. For the film before that, called Recollection (2015), I used already existing footage from Israeli fiction films that were shot in my hometown Jaffa throughout the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. These films excluded the Palestinian narrative while they documented the city, so I basically shifted the focus of these films to their hidden backgrounds and created a new narrative with them. I’m now trying to reuse already existing footage and images, because we have so many images already, and there is a lot of potential to dig deeper into these images and create new meaning. In fact, since we are not that mobile anymore, in the sense that we have all these limitations during the pandemic, it could open up all these new possibilities for us. To edit, to look back at images, to go through our old albums, you know? There’s a lot of space there for questions and reflections. When you shoot, you’re kind of occupied with the immediate, with reality, with the people. But when you work from home and you’re looking back at images that were already done, you have to reflect because you have to process them. I enjoy this a lot.

RW You do it so well. I saw An Unusual Summer and I loved it. I love to face a kind of uncertainty, that feeling of “what’s going to happen?” You do put the viewer a little bit on the wrong track sometimes. It’s a crime mystery and it’s an homage to your father, it’s many things at the same time. I love it when you watch something and you’re not quite sure what you’re looking at all the time. Is that something that you do deliberately, to allow for this kind of reflection you were talking about?

KA I think it goes both ways. I think I was very lucky to find this footage from a surveillance camera my father installed to find out who was repeatedly breaking his car window. I mean, it’s not every day that you find surveillance camera footage recorded on the corner of your childhood home. For me, this was quite incredible. I couldn’t believe that this material existed! I was watching it and later on actually started thinking that the surveillance camera and this kind of film style where the camera is fixed and just recording, might ultimately be the best form of cinema. This is, in fact, where the camera is operating without any intervention by humans. The camera is just staying where it is and, I have to say, my father really placed the camera in such a fantastic position. He managed to capture everything happening in the neighbourhood with the purpose of knowing who had thrown that stone at his car window. He had a purpose, and he didn’t move the camera. I had to watch everything for the edit and take notes of everything. It was really crazy work. My friends were making jokes about me going crazy. I was observing a civilian camera for months and months. It was like I myself became a detective. At first, I was looking for this person throwing the stone. I couldn’t find him, but then I started seeing other things. Finally, it became a film, in a way, that was making itself. You know that life isn’t always that exciting, not like what we’d see in some traditional films. You know that some days just go on, without anything really happening. And then, suddenly, something is happening. This is the challenge that I always face: I deal with finding this balance between making a film and being truthful to the way things are.

RW You mentioned, that in a way, the film made itself. What did you mean by that?

KA That at some point in the editing process, you start to follow certain patterns that weren’t planned. This is actually, for me, where it becomes very exciting. Around 25 or 30 minutes into the film, it just becomes so hypnotic in a way. It’s not just about a certain story anymore, but about a kind of magic that is happening, which is difficult to explain. This occurs more with these kinds of films, where I deal with already existing footage. I am being invited to places of which I didn’t shoot the material – I just found it, so it kind of puts me in a situation where I have to follow the material.

RW You have to follow the traces.

KA Exactly, the traces. That’s why I like to use this description of the film making itself. In the way that the structure is also an open structure. I mean, it is a structure that was based on the notes that I took. And, slowly, I constructed… I wouldn’t say a story, because it’s a structure which is trying to construct a point of view about this one corner. Of course, you’re still selective. You’re seeing what you want to see, and you select what you want to select.

RW There are these elements that you mentioned, of almost having a narrative, but also, as you said already, it’s in parts very meditative.

KA Absolutely. The idea is also that all this watching and investigating finally, for me, becomes the investigation of these small details of life, like someone walking and then standing in front of the camera. When you have this ability to watch for so long and to meditate on life, you find a lot of traces of poetic expression. These moments of poetic expression are what I like in cinema. Within the madness of the world, within political uncertainties, within all these conflicts, there is a kind of repetition in a history that’s almost elliptical. This poetic expression is very important to get out of a situation and to find new meanings.

RW Do you think this look at poetry and its power is, in that way, also part of your cultural background?

KA I always liked poetry. In fact, I think poetry is a liberating form. Of course, in Palestine, we have a very long and rich tradition. In general, we have this in the Arabic language. This is something that I’ve always enjoyed. Even in school, we had a lot of classes of reading and writing poetry. When you’re a child, it’s a nightmare though. You start to imitate what you read and try to write very complex language. What’s so interesting about finding these traces of poetic expression, is finding the simplicity. I think it was Pushkin who said that poetry has to be simple and sometimes stupid even. This is something that I enjoy a lot, and it is something that’s so liberating and even universal, because you can connect with others through it. I think the greatest ability of poetry is to reach out to the people that we don’t know.

RW There was this exhibition that I really liked that was called The Epic & the Everyday (1994). I guess in your film or in the way that you talk about poetry, you should reverse and say: it’s the Everyday and the Epic.

KA I like this definition, this relation between the everyday and the epic, because for me, the everyday is epic.

![]()

RW What I also connected with your films, is this feeling of being a child, having these obsessions with secrets or wanting to know what’s going on. You can see the way people behave when they think nobody’s looking or when they’re home alone or whatever. It’s sometimes very mundane stuff, but sometimes also interesting. Your film really captures that.

KA For that reason I also use the narration of my niece, who was nine years old at the time. I like this point of view of a child, looking at this footage that was shot before she was even born. Her observations are very simple, naive even. This naivety also has its own poetic aspects. When I was thinking about a film we could select together, I went back to Tsai Ming-liang, because, for me, he’s a filmmaker who works with very simple elements and it always works so well. He makes these reflections about almost everything in life.

RW It’s again the epic in the everyday.

KA Exactly. It’s so fascinating. You have this film called Walker (2012). It’s with the monk that walks, step by step from his place to the temple. If you would pitch that to someone, they’d say you are crazy. But when Tsai does it, it just works, you know? I really admire Tsai Ming-liang for that. I also had to think about Stray Dogs (2013), because he just beautifully manifests this quality in so many scenes, whether it’s the woman combing the child’s hair or the man staring at the reflections of a wall in an abandoned building. There are really so many scenes in which, in fact, it’s not only the cinema as a kind of gallery, it’s humanity as a gallery. What I mean is that it gives these endless possibilities of reflection. It’s an exposition of so many things. So, when we speak of cinema, we think: “It’s cinema, it’s a movie”. But the gallery in that sense is so many more things.

RW The way you interpret the gallery here maybe steers us a little bit towards your own films as well. Maybe we should consider that working with found footage is a more interesting way of making film, because there is already so much footage we really don’t look at. You could interpret the gallery almost as a universe of images.

JL Kamal, I’m very curious about how you see yourself in that equation between cinema and the gallery.

KA I think this is something that I very much appreciate and like about Rotterdam. It’s a place where things are not entirely defined. Definitions can be difficult. For example, when I fill in an application form for a film, I always have to answer whether it’s “documentary”, “fiction” or “experimental”. Some people do all of that at the same time! That’s why I think things should be presented more freely. It allows for this variety of expressions that exists within cinema and art. It’s a place to coexist, a place to live and to have a dialogue in.

![F3 Stills from An Unusual Summer, Kamal Aljafari, 2020]()

RW I think one of the great things about IFFR is that there’s this space for ambiguity. It’s not straightforward, like only this type of film or this type of art. You know it can be something in between, just like your films. There’s the art space and there’s the commercial cinema – they both have their own rules, restrictions, and possibilities. The festival is somewhere in between, because it can offer the context that the art space can give, but it can also be a projection machine in the classic sense of the theatre. But I do think that there are big differences, when you compare gallery spaces with film spaces. I mean, film is projection. It’s flat, it’s light. A gallery space is a physical space. I get very excited about the possibilities of translating film to these kinds of spaces. There have been many attempts. Many films have been shown in gallery spaces or have been converted to little installations that do something with the film. But to be super honest, I’m usually quite disappointed with the results. It hasn’t really taken off yet. The possibilities are certainly there, but only a few baby steps have been taken. I remember when I was at the festival, we did these films that were made for the public space. Three filmmakers were commissioned to make films that were to be projected on buildings. Usually, when you see moving images in the public space, it’s an advertisement or some news media. How would cinema work in a space like that? That’s an avenue of thought I was always quite interested in, but it’s hard to do it really well. When I started working for the festival, I didn’t have a very strong film background – it was more in art. I thought that one of the strategic threats for the festival would be this pressure to become more commercial, to become more glamorous, or to become more like any other film festival. I wanted to maintain the integrity of IFFR, and I felt pretty confident about that, because I was coming from a scene where integrity is even more important. Integrity in the film industry is, obviously, also important, but in the art world, even more so. So, I felt confident that I could defend that kind of integrity in Rotterdam. Cinema has always been the core of the festival. And then there’s the greyer area between art and cinema, which takes places on the fringes of the festivals. You could say the core business of the festival was the approximately 150 feature films, and the rest was part of the side programmes. I wanted to reverse that. I wanted the side programmes in the centre and have the feature films around it. I don’t know if we succeeded, but for me, that was a way to not only protect the integrity of the film festival, but also to embrace the fact that Rotterdam’s a bit of an anomaly. It’s a huge festival that’s important in the film industry, and important for audiences, but absolutely not mainstream. Usually, when you reach a scale like this, it’s important that you remain a mainstream festival. Miraculously, IFFR managed to be popular and edgy at the same time. That’s a thing of beauty, because that’s so rare.

KA We are surrounded by the mainstream everywhere, so why would a film festival do the same thing? If you turn on the TV or when you even just live in a city, you’re immersed in commercials and projections of things to sell. There’s no reflection whatsoever about anything meaningful. I think that film festivals should be the place of reflection, of raising questions about our being and this can never be mainstream, it has to be more open for interpretations, for questioning.

JL I was thinking about what Rutger was saying, about these endless possibilities of the art space and I wondered, Kamal, if you’d have total control over the experience, how would you like your work to be perceived?

KA I actually experienced when Recollection was screened in a cinema. It’s a very slow film. The whole film is constructed around a person that you never see, who’s walking inside the found images. I think that this is a place where some people can enjoy it, but you cannot make such a film for everyone. When I saw the same film in a gallery space, I also really liked it. I liked that people could decide to leave or stay longer. I’m always surprised that people do stick around so long, because there’s always the option to just leave. Some people don’t stay long and that’s fine with me. It’s a kind of contract you have with people: when you enter this space, you can decide how much time you are spending there. I find that very democratic in a way, and that’s the difference between a normal cinema setting and the gallery space. So, one could say that the gallery space is more democratic. People can come and go whenever they want, whereas in the cinema, you have to sit down and stay for the duration of the film. So I’d want to have the two options: having that normal, cinema setting, and the place where one is more mobile and free.

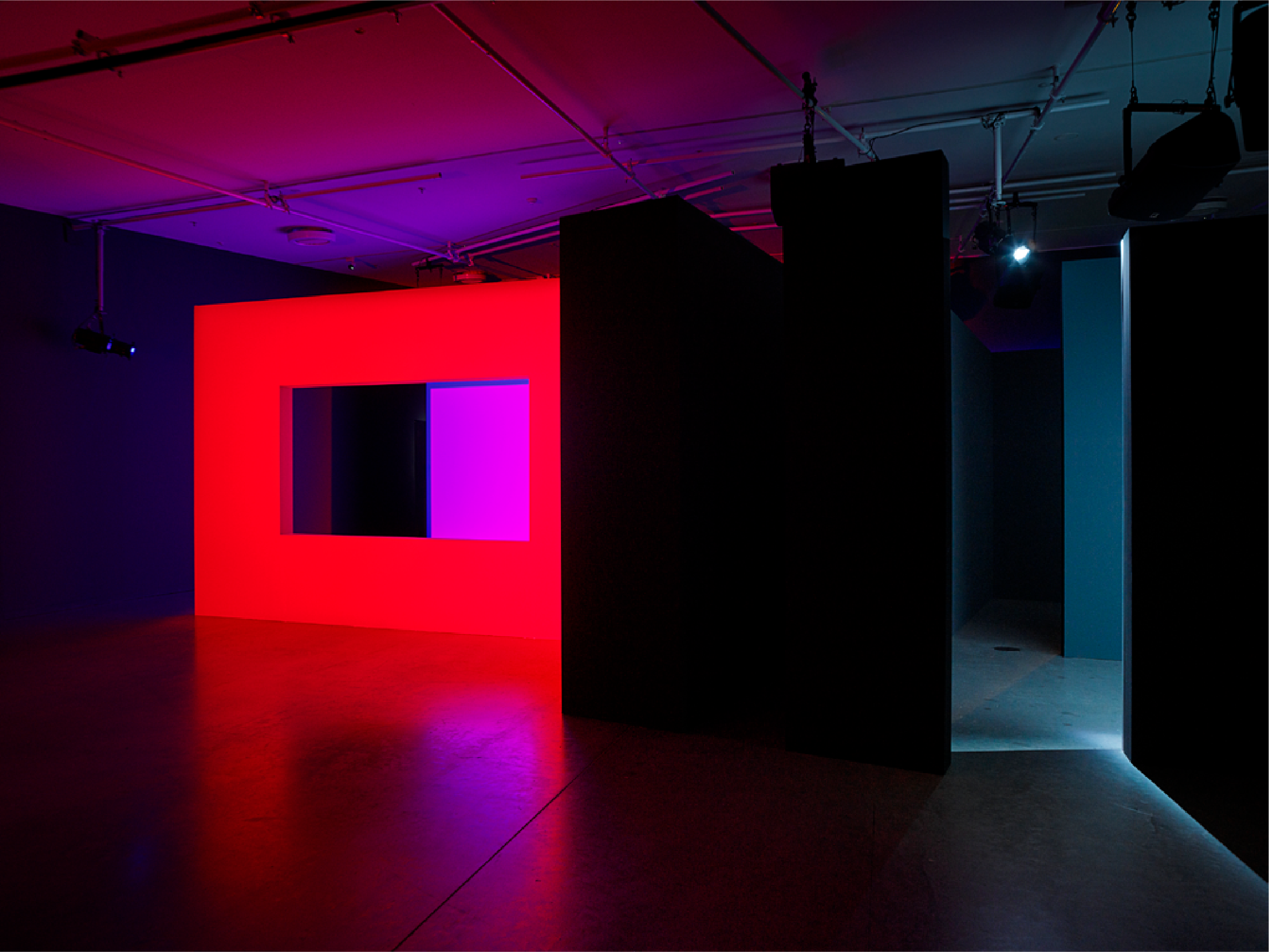

![F4 Leopold Emmen, Filmwork for Eye: 5 Scenes at a Walking Pace, 2021 ©Studio Hans Wilschut]()

RW My theory would be that we have all watched so many films that we can look at the world around us, as if we are in film, just walking down the street or any other mundane situation. It might sometimes be easier or harder to picture it like this, but if you’re in a gallery space… if you’re guided in the right way by the people who made the exhibition, you can experience these visits to the gallery as if you’re watching a film. I saw one example recently that I really liked. It was part of this anniversary exhibition called Vive le cinéma!, which was a collaboration between IFFR and Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. There was this Leopold Emmen installation called 5 Scenes at a Walking Pace (2021). Nanouk Leopold is also a filmmaker and together with visual artist Daan Emmen, she made this abstract, almost sculptural installation, where all the different elements could also be like film sets, like a window with a wall or a door. But basically, they were just white objects. They had some scripting going on, with changes in the light and music, so the lights and shadows could shift, and the music would suddenly change in atmosphere, and become suspenseful and stuff like that. I thought that it was an unusually cinematic experience, because it plays with the language of film, while allowing you to walk around it to see how the installation works. Because we have cinema tattooed on our brain and in our eyes, you can look at a work like that as if it were a film. But you’re really seeing anything. Just a couple of objects with some lights on it. It’s connected to this idea that everybody watching a film, is making their own film anyway, because that’s what’s happening in your brain when you’re watching. Surely, Kamal, you have seen different responses from people who are watching your films, because everybody makes their own film in their own head.

KA I wish I had seen this exhibition!

RW It’s the kind of installation that should have just been bought and installed permanently, because if you try to explain to people why there is a film museum in the first place – apart from conserving films – this would be a perfect example.

Moderated by IFFR programmer Janneke Langelaan.

RW We’ve never met before, right?

KA No, but your face is familiar. I think I’ve seen you around the film festivals, probably many years ago in Rotterdam as well. Rotterdam was my first festival ever, back in 2003. I was still living in Cologne at that time, so it was very close.

RW Were you here with a film or were you just visiting?

KA I came with a bunch of students to watch movies. Rotterdam was the place to be, back then. All these Asian films were coming into the festival, so we had to come and watch them.

RW Just curious – where are you right now?

KA I’m in Berlin. I’ve been living here since 2011.

RW I lived there as a student for about half a year. It was right after Die Wende, when the Wall came down. It was an amazing time, a collision of two worlds, like history happening right in front of your eyes.

KA Yeah, that’s a bygone era.

RW It’s just a big city now.

KA It’s a normal place again.

RW But still a nice place to live. I’m calling you from my home in Rotterdam. I started out working in the art world as a curator and a writer of essays about art theory. Somehow, by miracle almost, I became the director of IFFR. They couldn’t find anybody else to do it, I guess. During my time as a curator, I think I organised around one hundred exhibitions. I was quite tired of constantly coming up with new ideas and spending that energy you need to give to these exhibitions, so I was ready for something new. Now I’m working for a debate institute [Arminius, ed.]. I don’t know if you’re familiar with this kind of format, but in the Netherlands and some other places in Europe, you have these places where public debate is organised. Public debate is considered to be highly important to democracy here, so there’s some funding to make them take place, which is a nice thing to do. Now, I’m also in the middle of a super scary and fun creative project, which I’m very excited about: I’m making a short film. I finally get to be in a slightly more creative position. You know, working at the debate institute is fine and the job at IFFR was super nice, but it’s not very creative work – you’re more part of management, trying to make a place for filmmakers and artists to share their work. I feel happy and kind of privileged that I’m now in a position to make something of my own.

KA That sounds beautiful! I’m in my own place as well. I’m editing this new film and dealing with all this technology. Basically, I’ve worked from home for many years now. The last three films I did, were mostly made with already existing footage that I, in fact, didn’t shoot.

RW I saw two of your films, I saw An Unusual Summer (2020) and…

KA Recollection, maybe?

RW It’s with the numbers in the end…

KA Ah! It’s a Long Way from Amphioxus (2019). It’s a strange movie.

RW No, it’s lovely!

KA I shot it in Berlin, in the so-called Ausländerbehörde, which is the building where people go to apply for asylum, or even just a normal residency. For the film before that, called Recollection (2015), I used already existing footage from Israeli fiction films that were shot in my hometown Jaffa throughout the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. These films excluded the Palestinian narrative while they documented the city, so I basically shifted the focus of these films to their hidden backgrounds and created a new narrative with them. I’m now trying to reuse already existing footage and images, because we have so many images already, and there is a lot of potential to dig deeper into these images and create new meaning. In fact, since we are not that mobile anymore, in the sense that we have all these limitations during the pandemic, it could open up all these new possibilities for us. To edit, to look back at images, to go through our old albums, you know? There’s a lot of space there for questions and reflections. When you shoot, you’re kind of occupied with the immediate, with reality, with the people. But when you work from home and you’re looking back at images that were already done, you have to reflect because you have to process them. I enjoy this a lot.

RW You do it so well. I saw An Unusual Summer and I loved it. I love to face a kind of uncertainty, that feeling of “what’s going to happen?” You do put the viewer a little bit on the wrong track sometimes. It’s a crime mystery and it’s an homage to your father, it’s many things at the same time. I love it when you watch something and you’re not quite sure what you’re looking at all the time. Is that something that you do deliberately, to allow for this kind of reflection you were talking about?

KA I think it goes both ways. I think I was very lucky to find this footage from a surveillance camera my father installed to find out who was repeatedly breaking his car window. I mean, it’s not every day that you find surveillance camera footage recorded on the corner of your childhood home. For me, this was quite incredible. I couldn’t believe that this material existed! I was watching it and later on actually started thinking that the surveillance camera and this kind of film style where the camera is fixed and just recording, might ultimately be the best form of cinema. This is, in fact, where the camera is operating without any intervention by humans. The camera is just staying where it is and, I have to say, my father really placed the camera in such a fantastic position. He managed to capture everything happening in the neighbourhood with the purpose of knowing who had thrown that stone at his car window. He had a purpose, and he didn’t move the camera. I had to watch everything for the edit and take notes of everything. It was really crazy work. My friends were making jokes about me going crazy. I was observing a civilian camera for months and months. It was like I myself became a detective. At first, I was looking for this person throwing the stone. I couldn’t find him, but then I started seeing other things. Finally, it became a film, in a way, that was making itself. You know that life isn’t always that exciting, not like what we’d see in some traditional films. You know that some days just go on, without anything really happening. And then, suddenly, something is happening. This is the challenge that I always face: I deal with finding this balance between making a film and being truthful to the way things are.

RW You mentioned, that in a way, the film made itself. What did you mean by that?

KA That at some point in the editing process, you start to follow certain patterns that weren’t planned. This is actually, for me, where it becomes very exciting. Around 25 or 30 minutes into the film, it just becomes so hypnotic in a way. It’s not just about a certain story anymore, but about a kind of magic that is happening, which is difficult to explain. This occurs more with these kinds of films, where I deal with already existing footage. I am being invited to places of which I didn’t shoot the material – I just found it, so it kind of puts me in a situation where I have to follow the material.

RW You have to follow the traces.

KA Exactly, the traces. That’s why I like to use this description of the film making itself. In the way that the structure is also an open structure. I mean, it is a structure that was based on the notes that I took. And, slowly, I constructed… I wouldn’t say a story, because it’s a structure which is trying to construct a point of view about this one corner. Of course, you’re still selective. You’re seeing what you want to see, and you select what you want to select.

RW There are these elements that you mentioned, of almost having a narrative, but also, as you said already, it’s in parts very meditative.

KA Absolutely. The idea is also that all this watching and investigating finally, for me, becomes the investigation of these small details of life, like someone walking and then standing in front of the camera. When you have this ability to watch for so long and to meditate on life, you find a lot of traces of poetic expression. These moments of poetic expression are what I like in cinema. Within the madness of the world, within political uncertainties, within all these conflicts, there is a kind of repetition in a history that’s almost elliptical. This poetic expression is very important to get out of a situation and to find new meanings.

RW Do you think this look at poetry and its power is, in that way, also part of your cultural background?

KA I always liked poetry. In fact, I think poetry is a liberating form. Of course, in Palestine, we have a very long and rich tradition. In general, we have this in the Arabic language. This is something that I’ve always enjoyed. Even in school, we had a lot of classes of reading and writing poetry. When you’re a child, it’s a nightmare though. You start to imitate what you read and try to write very complex language. What’s so interesting about finding these traces of poetic expression, is finding the simplicity. I think it was Pushkin who said that poetry has to be simple and sometimes stupid even. This is something that I enjoy a lot, and it is something that’s so liberating and even universal, because you can connect with others through it. I think the greatest ability of poetry is to reach out to the people that we don’t know.

RW There was this exhibition that I really liked that was called The Epic & the Everyday (1994). I guess in your film or in the way that you talk about poetry, you should reverse and say: it’s the Everyday and the Epic.

KA I like this definition, this relation between the everyday and the epic, because for me, the everyday is epic.

RW What I also connected with your films, is this feeling of being a child, having these obsessions with secrets or wanting to know what’s going on. You can see the way people behave when they think nobody’s looking or when they’re home alone or whatever. It’s sometimes very mundane stuff, but sometimes also interesting. Your film really captures that.

KA For that reason I also use the narration of my niece, who was nine years old at the time. I like this point of view of a child, looking at this footage that was shot before she was even born. Her observations are very simple, naive even. This naivety also has its own poetic aspects. When I was thinking about a film we could select together, I went back to Tsai Ming-liang, because, for me, he’s a filmmaker who works with very simple elements and it always works so well. He makes these reflections about almost everything in life.

RW It’s again the epic in the everyday.

KA Exactly. It’s so fascinating. You have this film called Walker (2012). It’s with the monk that walks, step by step from his place to the temple. If you would pitch that to someone, they’d say you are crazy. But when Tsai does it, it just works, you know? I really admire Tsai Ming-liang for that. I also had to think about Stray Dogs (2013), because he just beautifully manifests this quality in so many scenes, whether it’s the woman combing the child’s hair or the man staring at the reflections of a wall in an abandoned building. There are really so many scenes in which, in fact, it’s not only the cinema as a kind of gallery, it’s humanity as a gallery. What I mean is that it gives these endless possibilities of reflection. It’s an exposition of so many things. So, when we speak of cinema, we think: “It’s cinema, it’s a movie”. But the gallery in that sense is so many more things.

RW The way you interpret the gallery here maybe steers us a little bit towards your own films as well. Maybe we should consider that working with found footage is a more interesting way of making film, because there is already so much footage we really don’t look at. You could interpret the gallery almost as a universe of images.

JL Kamal, I’m very curious about how you see yourself in that equation between cinema and the gallery.

KA I think this is something that I very much appreciate and like about Rotterdam. It’s a place where things are not entirely defined. Definitions can be difficult. For example, when I fill in an application form for a film, I always have to answer whether it’s “documentary”, “fiction” or “experimental”. Some people do all of that at the same time! That’s why I think things should be presented more freely. It allows for this variety of expressions that exists within cinema and art. It’s a place to coexist, a place to live and to have a dialogue in.

RW I think one of the great things about IFFR is that there’s this space for ambiguity. It’s not straightforward, like only this type of film or this type of art. You know it can be something in between, just like your films. There’s the art space and there’s the commercial cinema – they both have their own rules, restrictions, and possibilities. The festival is somewhere in between, because it can offer the context that the art space can give, but it can also be a projection machine in the classic sense of the theatre. But I do think that there are big differences, when you compare gallery spaces with film spaces. I mean, film is projection. It’s flat, it’s light. A gallery space is a physical space. I get very excited about the possibilities of translating film to these kinds of spaces. There have been many attempts. Many films have been shown in gallery spaces or have been converted to little installations that do something with the film. But to be super honest, I’m usually quite disappointed with the results. It hasn’t really taken off yet. The possibilities are certainly there, but only a few baby steps have been taken. I remember when I was at the festival, we did these films that were made for the public space. Three filmmakers were commissioned to make films that were to be projected on buildings. Usually, when you see moving images in the public space, it’s an advertisement or some news media. How would cinema work in a space like that? That’s an avenue of thought I was always quite interested in, but it’s hard to do it really well. When I started working for the festival, I didn’t have a very strong film background – it was more in art. I thought that one of the strategic threats for the festival would be this pressure to become more commercial, to become more glamorous, or to become more like any other film festival. I wanted to maintain the integrity of IFFR, and I felt pretty confident about that, because I was coming from a scene where integrity is even more important. Integrity in the film industry is, obviously, also important, but in the art world, even more so. So, I felt confident that I could defend that kind of integrity in Rotterdam. Cinema has always been the core of the festival. And then there’s the greyer area between art and cinema, which takes places on the fringes of the festivals. You could say the core business of the festival was the approximately 150 feature films, and the rest was part of the side programmes. I wanted to reverse that. I wanted the side programmes in the centre and have the feature films around it. I don’t know if we succeeded, but for me, that was a way to not only protect the integrity of the film festival, but also to embrace the fact that Rotterdam’s a bit of an anomaly. It’s a huge festival that’s important in the film industry, and important for audiences, but absolutely not mainstream. Usually, when you reach a scale like this, it’s important that you remain a mainstream festival. Miraculously, IFFR managed to be popular and edgy at the same time. That’s a thing of beauty, because that’s so rare.

KA We are surrounded by the mainstream everywhere, so why would a film festival do the same thing? If you turn on the TV or when you even just live in a city, you’re immersed in commercials and projections of things to sell. There’s no reflection whatsoever about anything meaningful. I think that film festivals should be the place of reflection, of raising questions about our being and this can never be mainstream, it has to be more open for interpretations, for questioning.

JL I was thinking about what Rutger was saying, about these endless possibilities of the art space and I wondered, Kamal, if you’d have total control over the experience, how would you like your work to be perceived?

KA I actually experienced when Recollection was screened in a cinema. It’s a very slow film. The whole film is constructed around a person that you never see, who’s walking inside the found images. I think that this is a place where some people can enjoy it, but you cannot make such a film for everyone. When I saw the same film in a gallery space, I also really liked it. I liked that people could decide to leave or stay longer. I’m always surprised that people do stick around so long, because there’s always the option to just leave. Some people don’t stay long and that’s fine with me. It’s a kind of contract you have with people: when you enter this space, you can decide how much time you are spending there. I find that very democratic in a way, and that’s the difference between a normal cinema setting and the gallery space. So, one could say that the gallery space is more democratic. People can come and go whenever they want, whereas in the cinema, you have to sit down and stay for the duration of the film. So I’d want to have the two options: having that normal, cinema setting, and the place where one is more mobile and free.

RW My theory would be that we have all watched so many films that we can look at the world around us, as if we are in film, just walking down the street or any other mundane situation. It might sometimes be easier or harder to picture it like this, but if you’re in a gallery space… if you’re guided in the right way by the people who made the exhibition, you can experience these visits to the gallery as if you’re watching a film. I saw one example recently that I really liked. It was part of this anniversary exhibition called Vive le cinéma!, which was a collaboration between IFFR and Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. There was this Leopold Emmen installation called 5 Scenes at a Walking Pace (2021). Nanouk Leopold is also a filmmaker and together with visual artist Daan Emmen, she made this abstract, almost sculptural installation, where all the different elements could also be like film sets, like a window with a wall or a door. But basically, they were just white objects. They had some scripting going on, with changes in the light and music, so the lights and shadows could shift, and the music would suddenly change in atmosphere, and become suspenseful and stuff like that. I thought that it was an unusually cinematic experience, because it plays with the language of film, while allowing you to walk around it to see how the installation works. Because we have cinema tattooed on our brain and in our eyes, you can look at a work like that as if it were a film. But you’re really seeing anything. Just a couple of objects with some lights on it. It’s connected to this idea that everybody watching a film, is making their own film anyway, because that’s what’s happening in your brain when you’re watching. Surely, Kamal, you have seen different responses from people who are watching your films, because everybody makes their own film in their own head.

KA I wish I had seen this exhibition!

RW It’s the kind of installation that should have just been bought and installed permanently, because if you try to explain to people why there is a film museum in the first place – apart from conserving films – this would be a perfect example.